Research

Can Algorithms Discriminate?

Fideres investigates algorithmic mortgage discrimination in the US.

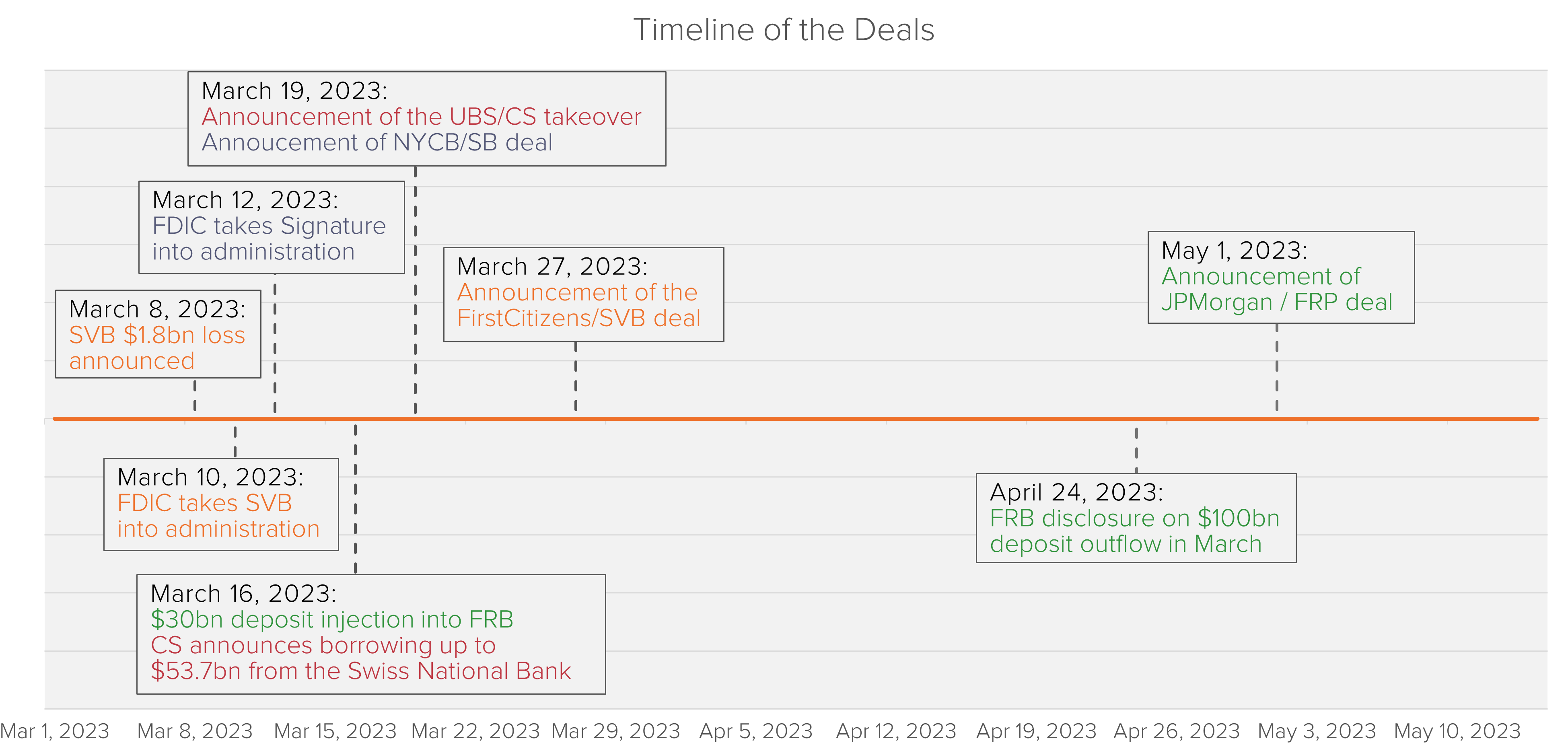

Over the course of a few weeks in March 2023, the global banking sector saw a bank run on the second-largest bank in Switzerland and three small- to mid-size U.S. banks. The resulting turmoil in the banking industry triggered hectic responses by regulators to prevent the potential spread of the crisis. The affected banks were sold off at deep discounts in relation to the fair value of the banks’ assets, resulting in record gains for the acquiring banks, while leaving the shareholders and holders of subordinated bonds of the target banks with billions in losses. The record discrepancy between the compensation received by shareholders and the fair value of the banks’ assets raises important questions about the initial valuation and the deal process involved.

The failures of First Republic Bank (FRB), Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank (SB) ranked as the second-, third- and fourth-largest bank failures in U.S. history, respectively, dwarfed only by the collapse of Washington Mutual during the 2007–2008 Great Financial Crisis. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) subsequently assumed control of these banks and facilitated the sales of SB to New York Community Bancorp, SVB to First Citizens and FRB to JPMorgan. In each of these three transactions, FDIC declared these banks insolvent and the shareholders experienced total losses.

In Switzerland, the financial market authorities orchestrated a deal between UBS and its rival Credit Suisse (CS), due to concerns about the potential collapse of the latter and the contagion risk to the domestic as well as global financial system. As part of this transaction, holders of CS’s then CHF 16bn outstanding Additional-Tier-1 bonds (AT1s) saw their investments completely written down. CS shareholders received compensation at CHF 0.76 per share, even though the shares were trading at CHF 1.86 on the last trading day preceding the agreement. Considering the fair value of the acquired net assets reported by UBS at the end of Q21, the implied value of one CS share was at approximately CHF 7.33, which is CHF 6.57 higher than what was paid to CS shareholders.

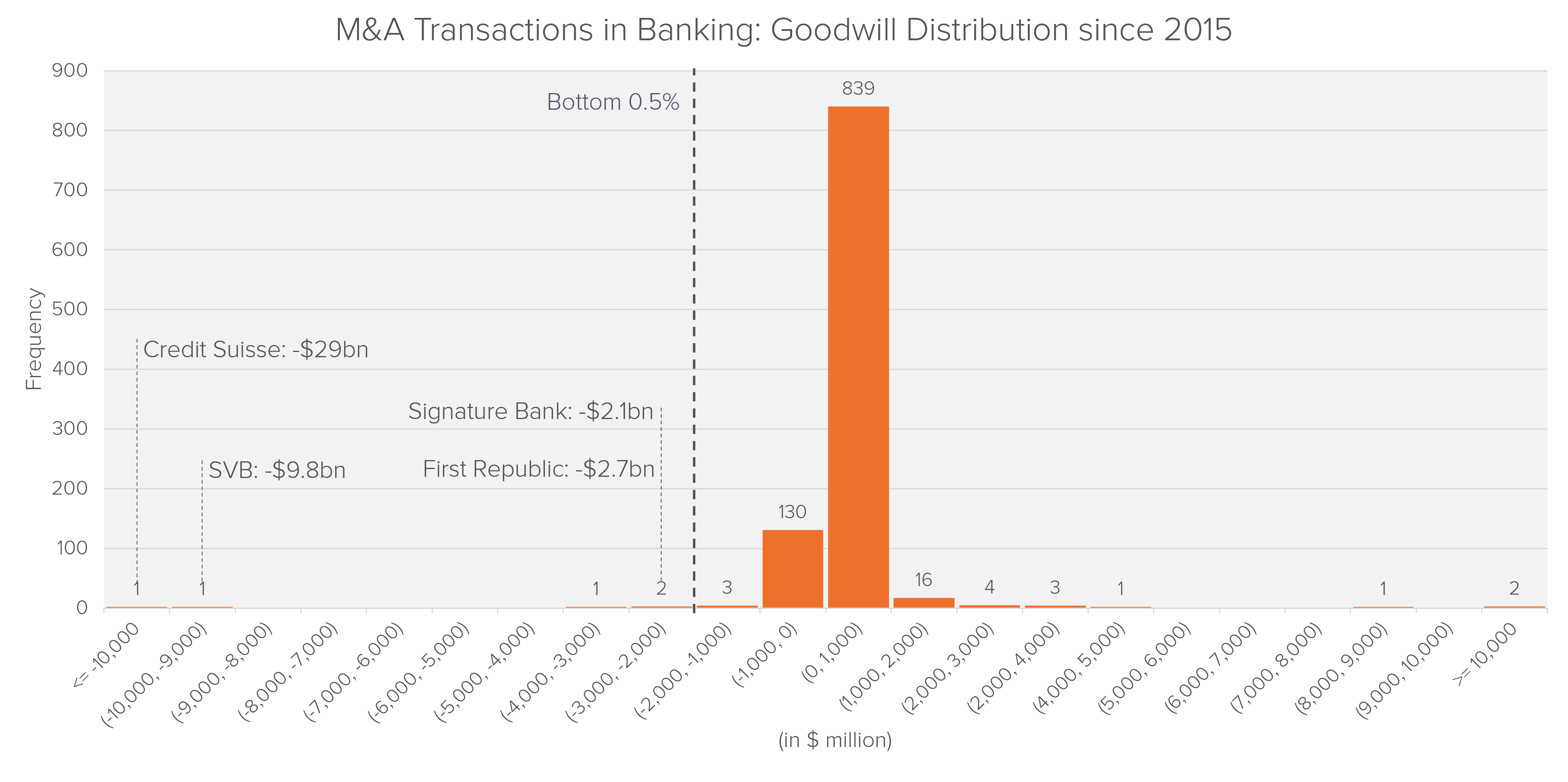

The unprecedented magnitude of shareholder losses is reflected in an accounting measure known as goodwill. In the context of M&A transactions, goodwill denotes the difference between the net asset value2 of the acquired company (also known as the target company) and the purchase price paid by the buyer (a.k.a. the acquirer). Typically, an acquirer pays a premium to a target company’s shareholders, as a compensation for intangible gains from the deal, e.g., synergy effects between the two businesses or the brand strength of the target company. This results in positive goodwill.

However, each of the four deals mentioned above resulted in a record amount of reported negative goodwill (or bargain purchase gain), totalling $44bn.3 The following table summarises the key information of the deals according to the latest SEC filings.

| Target | Acquirer | Consideration Paid (in $ mil.) | Fair Value of Net Assets (in $ mil.) | Negative Goodwill (in $ mil.) |

| Signature Bank | New York Community Bancorp | 85 | 2,227 | 2,142 |

| Silicon Valley Bank | First Citizens | 35,650 | 45,474 | 9,824 |

| First Republic Bank | JPMorgan Chase | 67,899 | 70,611 | 2,712 |

| Credit Suisse | UBS | 3,710 | 32,771 | 28,925 |

It is not unheard of to see bargain prices in M&A deals, but they are rare. Data from S&P indicates that, since 2015, only 13.5% of all transactions involving banks and thrift institutions were completed with a negative goodwill. More strikingly, the four deals are among the five deals with the largest negative goodwill, i.e., fall within the bottom 0.5% of the goodwill distribution.4

Notably, the sale of CS to UBS stands out as a record-breaker, resulting in an extraordinary gain of $28.9bn for UBS.5 This picture holds even when looking back over a longer period. There are only a handful of deals that have ever reported comparable negative goodwill figures, primarily during the tumultuous times of the Great Financial Crisis.6 For instance, the acquisition of the British insurer HBOS by Lloyds Banking Group resulted in a negative goodwill of £11.2bn.7 Similarly, Bear Stearns was acquired by JPMorgan in a fire-sale after it collapsed with a reported negative goodwill of $8.3bn.8 Lastly, Barclays gained £2.3bn from the acquisition of the North American business of Lehman Brothers.9 These still represent only a fraction of negative goodwill in the CS deal.

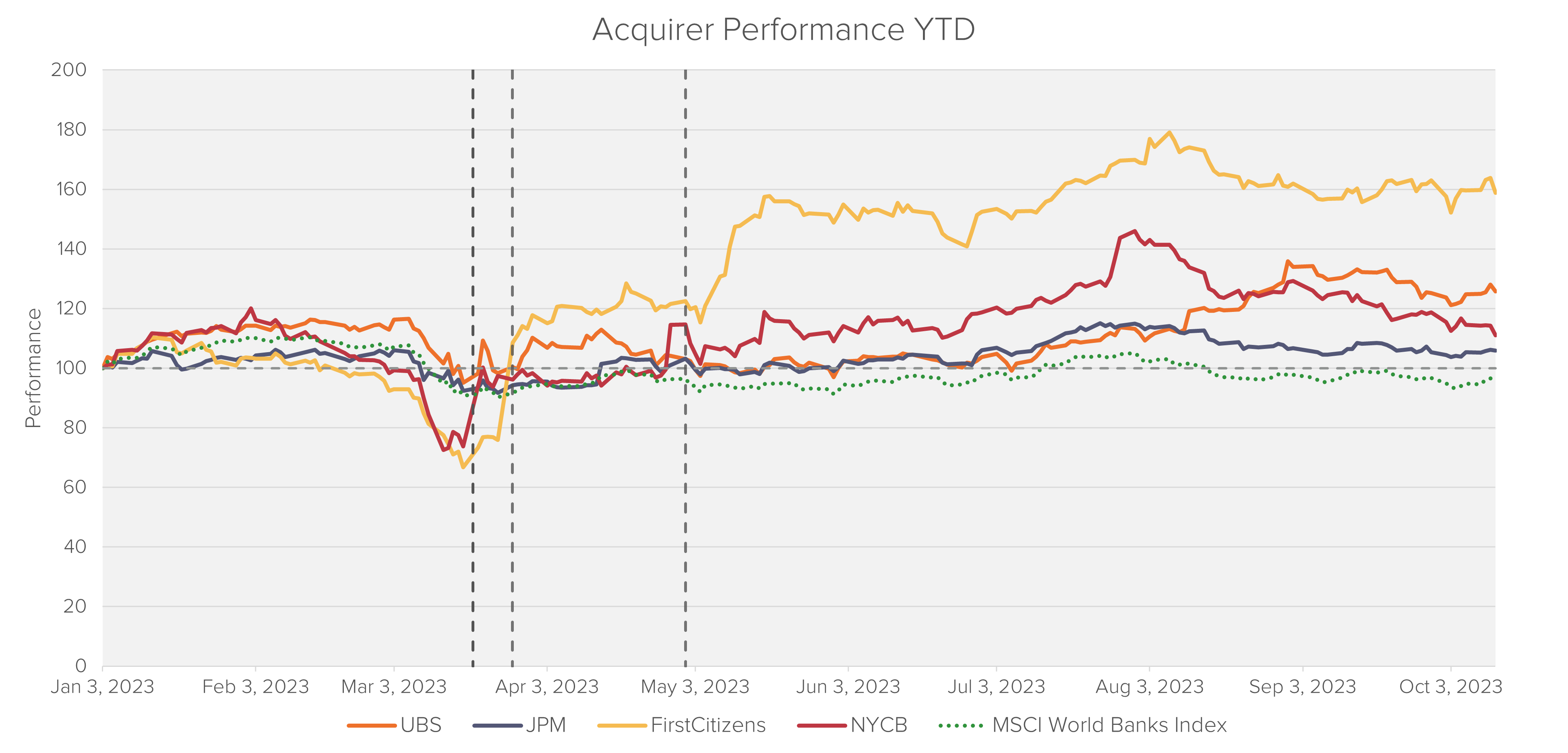

Although these deals do come with expenses, such as the CS/UBS deal involving the integration of two Global Systemically Important Banks’ systems, and associated risks, like the three U.S. deals involving depositors’ withdrawals, the market widely viewed these transactions as highly advantageous for the acquiring banks.

The chart below shows the year-to-date performance of the four acquiring banks in comparison to the MSCI World Banks Index. Banking stocks slid during the springtime turmoil and have shown relatively stable overall performance since then. In contrast, the four deals are perceived as favorable to the acquiring companies when examining the pure stock price gain since the announcement of the deals. Each of the stocks has outperformed the benchmark index year-to-date, demonstrating the favorable perception of these acquisitions on the acquirers.

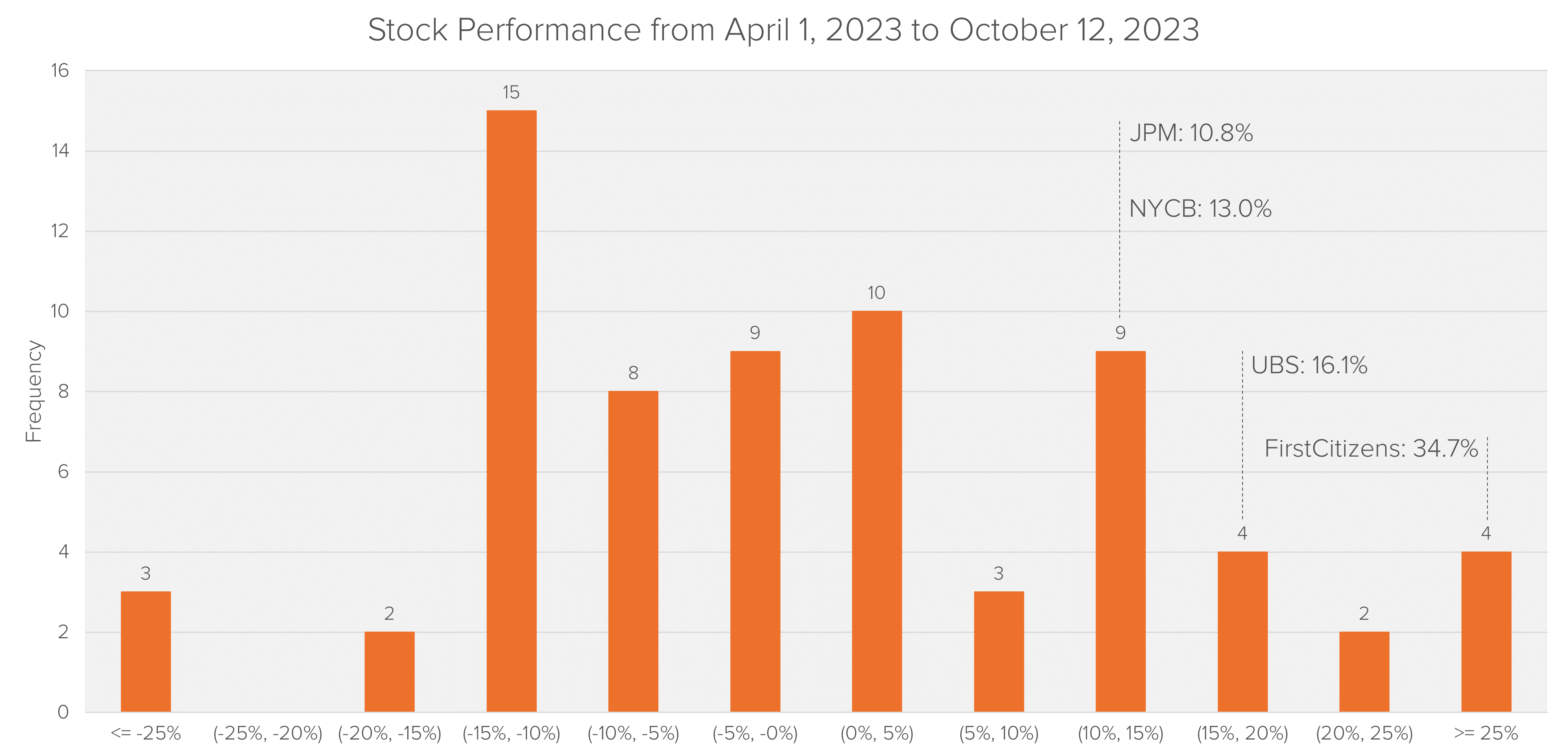

The chart below illustrates the stock return distribution of 69 banks globally from April 1, 2023 to October 12, 2023. Notably, the returns of the acquiring companies all fall within the top quartile of this distribution.

Fideres conducted a comprehensive examination of the four deals by running an event study analysis. This analysis isolates the impact of the deal announcement on the stock price while eliminating other factors. Two control variables are used: one accounting for general market movements, which is represented by a broad and relevant equity market index, and another accounting for the banking industry sector, represented by an industry-specific equity index.10 The excess return of the share price, after accounting for these effects, reflects the idiosyncratic and buyer-specific news and information, thus capturing the deal’s impact on the share price.

wpDataTable with provided ID not found!The above table shows the excess return for each buyer on the announcement day of the respective deal. Shareholders of acquiring companies have profited significantly from these acquisitions, achieving sizable excess returns compared to general equity markets as well as their peers in the banking sector. At the same time, the dollar value gain, measured as the pre-announcement market capitalization multiplied by the excess return on the announcement day, indicates the information absent to private investors when compared to the final reported negative goodwill. Specifically, the net gains for NYCB, FC, and UBS resulting from the acquisitions surpassed the market’s initial assessment following the announcements.

As all four of these aforementioned deals were orchestrated by regulatory authorities, investors in the targeted companies find themselves unable to exercise their typical rights to safeguard their investments, as they would in a standard M&A transaction during the deal process. Nevertheless, this does not preclude these investors from seeking redress through legal actions.

In cases where the target companies and other relevant parties have issued inaccurate statements regarding the causes of their failures, shareholders will have the option to initiate claims under Section 10b of the Securities and Exchange Act against company directors, officers, underwriters, and/or auditors.

For example, a recent complaint on behalf of former SVB shareholders claims damages against senior executives of SVB, members of the SVB’s board of directors, the underwriters of SVB’s public offerings, and KPMG, SVB’s auditor.13 The complaint alleges that “throughout the Class Period, some or all Defendants misrepresented the strength of the Company’s balance sheet, liquidity, and position in the market”, resulting in an artificially inflated stock price of SVB. Essentially, defendants allegedly underestimated the risks to the company’s business in light of central bank interest rate hikes, leading to declines in the valuation of its long-term loan portfolio, higher payable deposit rates, and decreased activity in private equity and venture capital investments, which are core to SVB’s business.

The UBS/CS deal has also triggered a number of complaints from former CS shareholders, AT1 bondholders, and employees, but these claims have slightly different cause of action.14 In August 2023, three model lawsuits were filed at the commercial court in Zurich, citing Article 105 of the Swiss Mergers Act, which was undermined at the time of the deal through emergency legislation.15 Former institutional and retail CS shareholders are seeking an adequate compensation for their shares, with the value to be determined by the court.16

At the same time, investors holding CS AT1 bonds are contesting the complete write-down of their investments in several filings in Switzerland and the U.S. While complaints by equity investors target only UBS, the filings on behalf of bondholders also challenge the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) and its decision to wipe out all AT1 bonds. These filings also involve claims of expropriation against the Swiss government. If successful, the decision by FINMA could be nullified, leading to the reinstatement of AT1 on UBS’s balance sheets. Alternatively, Swiss taxpayers might be required to cover the losses incurred by AT1 bondholders.17

Lastly, former and current employees are asserting legal claims concerning the removal of their contingent capital awards (a form of bonus akin to AT1 bonds) by FINMA.

Regulators emphasize their commitment to maintaining the arm’s length principle during the negotiation process of the aforementioned transactions, ensuring that the agreed purchase prices align with fair market values.18 However, it appears very questionable if this principle was upheld, given unprecedented large gains from negative goodwill realized by the acquiring banks. In particular, the rapid reversal in valuation, calls into question whether a proper fair value assessment has been conducted before agreeing on a sale of the target institutions at steep discount prices to the detriment of existing shareholders and holders of subordinated bonds.

The preceding analysis highlights the opportunity for shareholders and bondholders to scrutinize the valuation and deal procedures in these fire-sale mergers. To substantiate a claim for damages, it is imperative to conduct a tailored evaluation of counterfactual scenarios to ascertain the accurate fair value of the target company in each instance. Should it be established that the valuation was insufficient, and the deal process was flawed, there could be legitimate grounds for the target company’s shareholders and bondholders to pursue compensation.

1 Quarterly reporting | UBS Global

2 Measured as the fair value of company’s assets minus the fair value of their liabilities.

3 See also The $44bn bank bailout bonanza (ft.com)

4 The other deal in that percentile is the takeover of UBI Banca by the Italian banking group Intesa Sanpaolo with a reported negative goodwill of $3.6bn.

5 Initially, the negative goodwill was estimated at $34.8bn. UBS reported material re-valuations of CS’s lending portfolio.

6 The following goodwill numbers are taken from SEC filings. Figures from Standard and Poor’s may differ from the reporting.

7 sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1160106/000093041310002874/c61230_20f.htm

8 SEC Filing | JPMorgan Chase & Co. (gcs-web.com)

10 In this event study, the S&P 500 is used as the market index and the MSCI World Banks Index is used as the industry index. The regression is calibrated using a sample size of 500 business days.

11 For NYCB and UBS the excess return concerns the day after the announcement as the deal was disclosed on a Sunday.

12 The gain is measured as the pre-announcement market cap multiplied by the excess return on/after the announcement day.

13 See City of Hialeah Employees Retirement System et al v. Becker et al, Case No. 3:23-cv-01697

14 See How UBS’s $3.3bn Credit Suisse deal spawned $9bn of legal claims (ft.com)

15 See Dritte Klage von CS-Aktionären will hoch hinaus (finews.ch)

16 See Home Credit Us – LegalPass

17 See So nehmen CS-Investoren das Notrecht in die Zange (finews.ch)

18 See, for example, FDIC: PR-34-2023 5/1/2023

Nicolas joined Fideres in June 2023. He holds a MSc in Finance from the University of Liechtenstein and is currently completing a MSc in Economics and Policy at the King’s College London.

During his studies in Liechtenstein, Nicolas acquired work experience at the domestic Financial Market Authority, where he worked in the Asset Management and Markets division as well as in the Financial Stability team.

Fideres investigates algorithmic mortgage discrimination in the US.

The emerging pro-defendant class action landscape.

Automotive cartels and emissions technology.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330