Research

Which US Bank Will Fail Next?

Which US banks would be unable to meet minimum regulatory capital requirements to cover un-booked losses, which amount to $877bn.

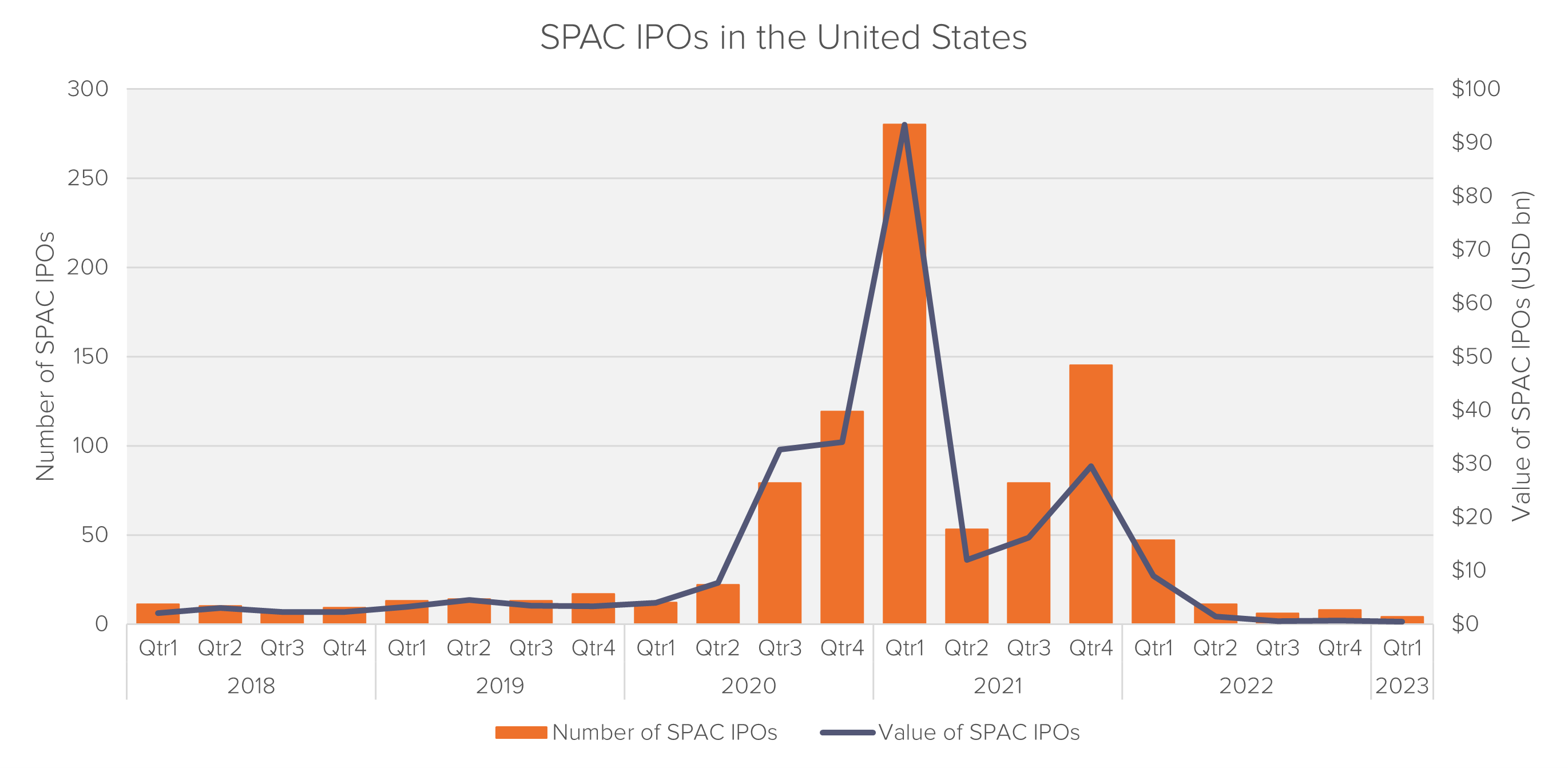

Once associated with lack of regulatory oversight in the 80s and 90s, SPAC IPOs proliferated in recent years with more than $150 billion capital raised in 2021 solely in the US. The majority of companies listed via a SPAC merger are now trading below their issuance price.

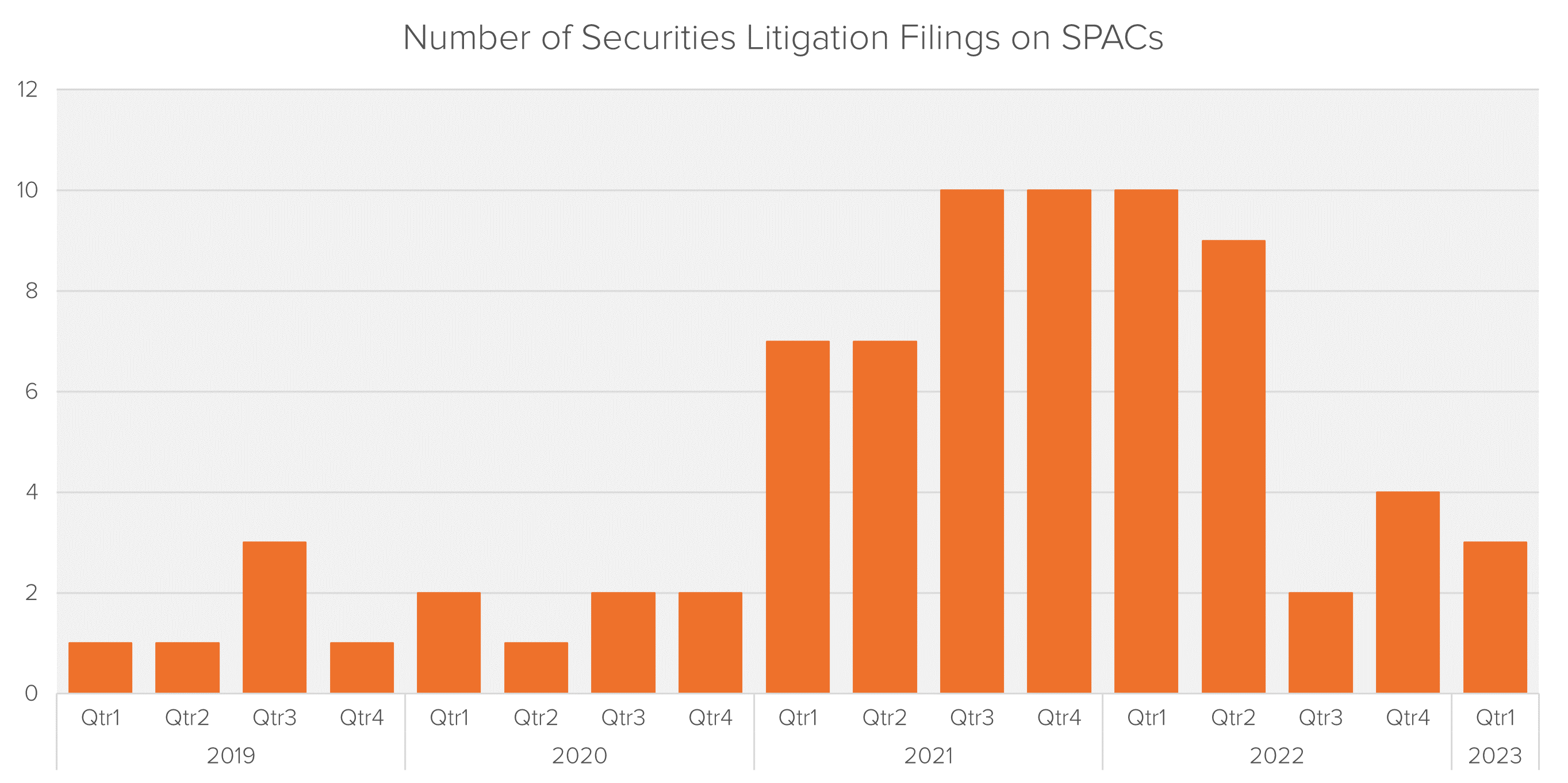

SPAC securities litigations have seen a sharp increase in the last two years. Typically, the plaintiffs of these securities class actions are SPAC IPO investors, suing either the SPAC sponsors, the target private company, or both. The allegations in the majority of these class actions relate to omissions or misrepresentations regarding the product of the target company, its operations, its capabilities or its client relations.

Source: Stanford Securities Class Actions Database

Source: Stanford Securities Class Actions Database

SPACs appear to be particularly prone to featuring in securities class actions which may be due to lower disclosure requirements, a buoyant stock market, and a focus on industries characterized by investors’ exuberance.

In addition, the prospect of having to return the raised capital to investors may have also pressured SPAC sponsors to settle for a less-than-ideal target company, and to misrepresent its true state of affairs in order to make it palatable to investors. It is important to note, however, that the time-incentive alone is unlikely to be sufficient to create an inference of intent in a 10b-5 case (as seen in re Stillwater Capital Partners Inc.2), although it may successfully be used in conjunction with other evidence.

Securities litigation on SPACs bring a unique set of challenges, as it presents characteristics of IPO fraud, merger frauds, as well as the challenges presented by the “non-operating” nature of the SPAC itself.

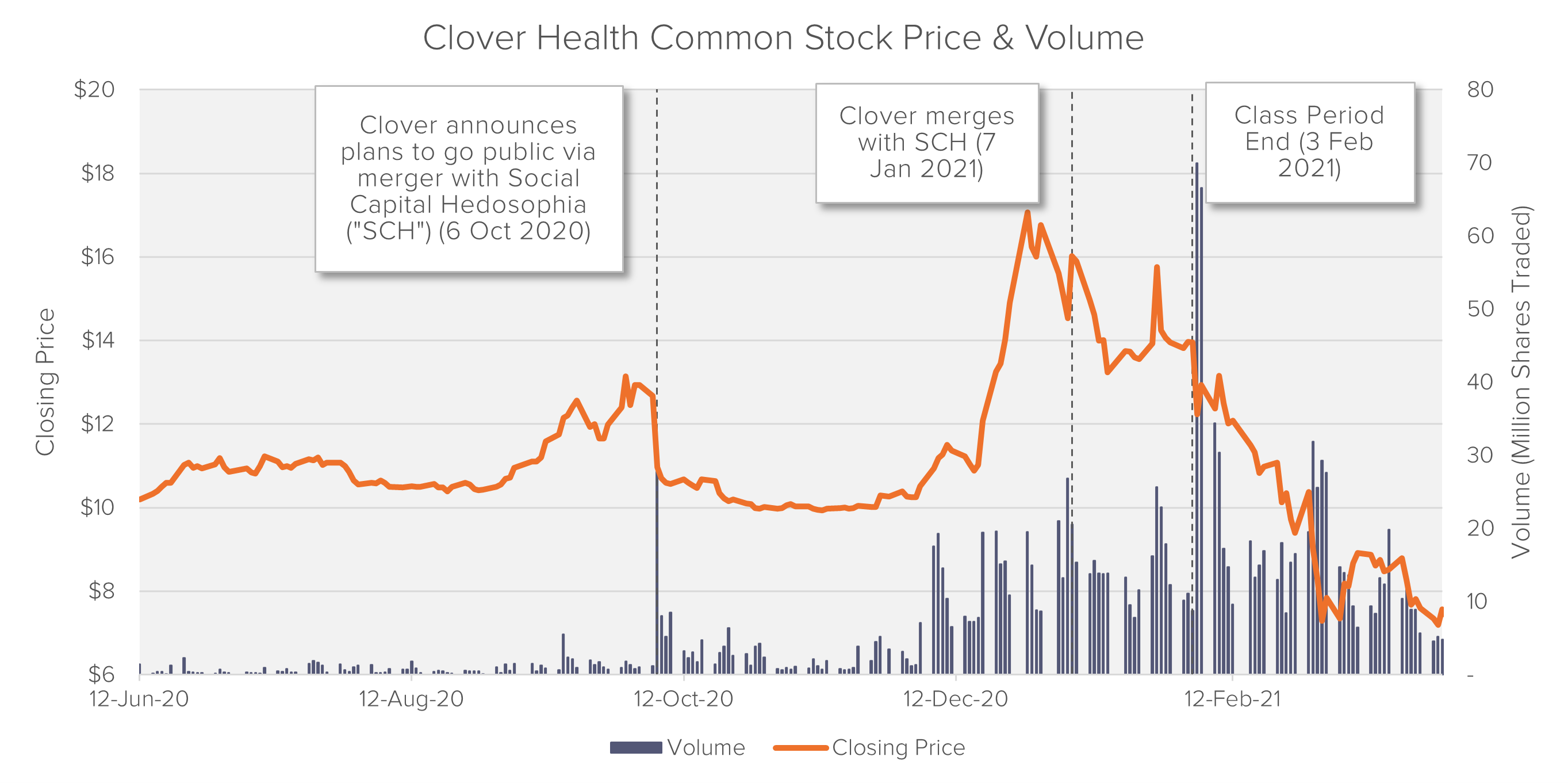

Unlike conventional IPOs, the de-SPAC process involves multiple entities, in particular the private target of a SPAC is a different entity than the SPAC itself. Using Clover as an example, the chart below shows a typical timeline for a de-SPAC.

From the merger announcement to the actual business combination, the defendant company in question is technically a “blank check” SPAC. However, like in Clover, the market commonly starts trading the SPAC shares in expectation of the business combination right after the merger announcement, making the price of the SPAC entity deviate significantly from its issue price. Therefore, it is often reasonable for the class period to start from the merger announcement rather than the actual business combination.

The class periods in SPAC securities litigations are usually short, and the event study regression window used in the analysis must be adjusted accordingly. In Clover and other recent SPAC securities litigations, experts have applied a shorter rolling regression window such as 60- or 90-days as opposed to a more common 120-days.

In addition, it is also common to apply an in-sample regression3 for the first rolling regression window, if the class period starts from the merger announcement. This is because SPACs are usually traded at or around their issue price before the merger announcement, which therefore is not representative of the stock price behavior after the announcement.

The Cammer court held that “[…] one of the most convincing ways to demonstrate [market] efficiency would be to illustrate, over time, a cause-and-effect relationship between company disclosures and resulting movements in stock price.”4

To evaluate this cause-and-effect relationship, financial experts analyze key days on which new value-relevant company information becomes public. A common choice for such news days are earnings release days. In the case of SPACs, these days may be scarce or even absent. Therefore, depending on the circumstances, the analysis may look at business combination related news days (e.g. shareholder voting days) or extend beyond the end of the class period.

Despite all these adjustments, this approach may still result in a relatively small number of objective news days. It is worth noting that courts have dispensed with the cause-and-effect factor, when other Cammer and Krogman factors support a finding of market efficiency.5 When certifying the Clover class, Judge Trauger stated “[Plaintiff’s expert’s] analysis is sufficient in light of the abundance of other reasons to conclude that the market for Clover securities was, in fact, efficient.”

In Clover, the Defendants claimed that the misstatements lacked price impact because Clover’s stock price dropped on the merger announcement date, when the allegedly false and misleading positive statements occurred which on the face of it should have increased the stock price.

This line of defense has been raised in various SPAC securities litigations, as it has often been observed that the share price declined on the day of the merger announcements.

In Clover, Judge Trauger ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, noting that courts recognize the so-called “price maintenance” theory that “a misrepresentation can have a price impact not only by raising a stock’s price but also by maintaining a stock’s already […] inflated price […].”6

SPAC IPOs are often structured to offer investors a unit of securities consisting of common stocks and warrants. Some time after the IPO but before the business combination, the SPAC’s common stocks and warrants may be traded separately on the exchange under separate symbols. It is also common for exchanges like the CBOE to create and list options on the common stock after the business combination.

Experts in securities litigations commonly apply the principles of Cammer and Krogman factors in evaluating the market efficiency of warrants and options, although many courts have taken the view that market efficiency for the common stock is sufficient to demonstrate that options and warrants also trade in an efficient market.7

Robert Chang, Head of Fideres’s Securities Litigation practice, is a financial market expert with extensive and broad-ranging experience in the areas of securities, commodities, derivatives and structured finance.

Since joining Fideres in 2014, Robert has been instrumental in helping institutional and retail investors to recover billions for his consulting and expert testifying work in over 30 landmark financial market investigations and litigations. His most recent successes include a $508 million partial settlement in the ISDAfix interest rate benchmark class action and a €1.4 billion settlement of securities fraud claims against Steinhoff International Holdings NV (second largest against a European issuer accused of securities fraud).

Robert’s team help law firms, regulators and investors across the globe in litigations and other disputes, from the initial claim filing, through dismissal, discovery, expert testimony and settlement. On his team, Robert is often the main architect for groundbreaking analyses and models used in key filings and testimonies.

Robert completed his MSc in Risk Management and Financial Engineering at Imperial College with distinction. Prior to this, he obtained a BSc Economics degree with distinction from Shanghai University of Finance and Economics.

Which US banks would be unable to meet minimum regulatory capital requirements to cover un-booked losses, which amount to $877bn.

A Fideres Special Antitrust Investigation into the UK CO2 Market.

Fideres identifies suspicious parallel price increases by all major UK mobile network operators.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330