Research

New York Taxi Medallions

Another rough ride for financial institutions?

The high price of academic journal subscriptions, the large profits, and the concentrated nature of the market has for some time generated concern that publishers are acting anticompetitively.1 Academic journals are two-sided platforms, that (like YouTube) must attract authors of content, and match those to readers of that content. Readers want access to the leading cutting-edge research in their field. Authors want to publish their research in a journal that is influential, widely read and which signals the quality of their research (particularly to their current and potential future employers and to those that determine academic funding). The value that a journal offers to readers therefore depends on the quality of the content that it attracts. Meanwhile the value that a journal can offer a prospective author depends heavily on the perceived influence of the journal, and hence its readership and the quality of the research alongside which the author’s work will feature.

Authors and readers also meet through unmediated networks where working papers can be freely posted and read. However, these lack quality control and so journals conduct peer-review processes to guarantee the minimum quality of the research that they feature. This attracts readers (and increases their willingness to pay) and authors, since both want to read/publish in high quality journals (and both exert cross-platform network effects that lead to beneficial feedback loops).

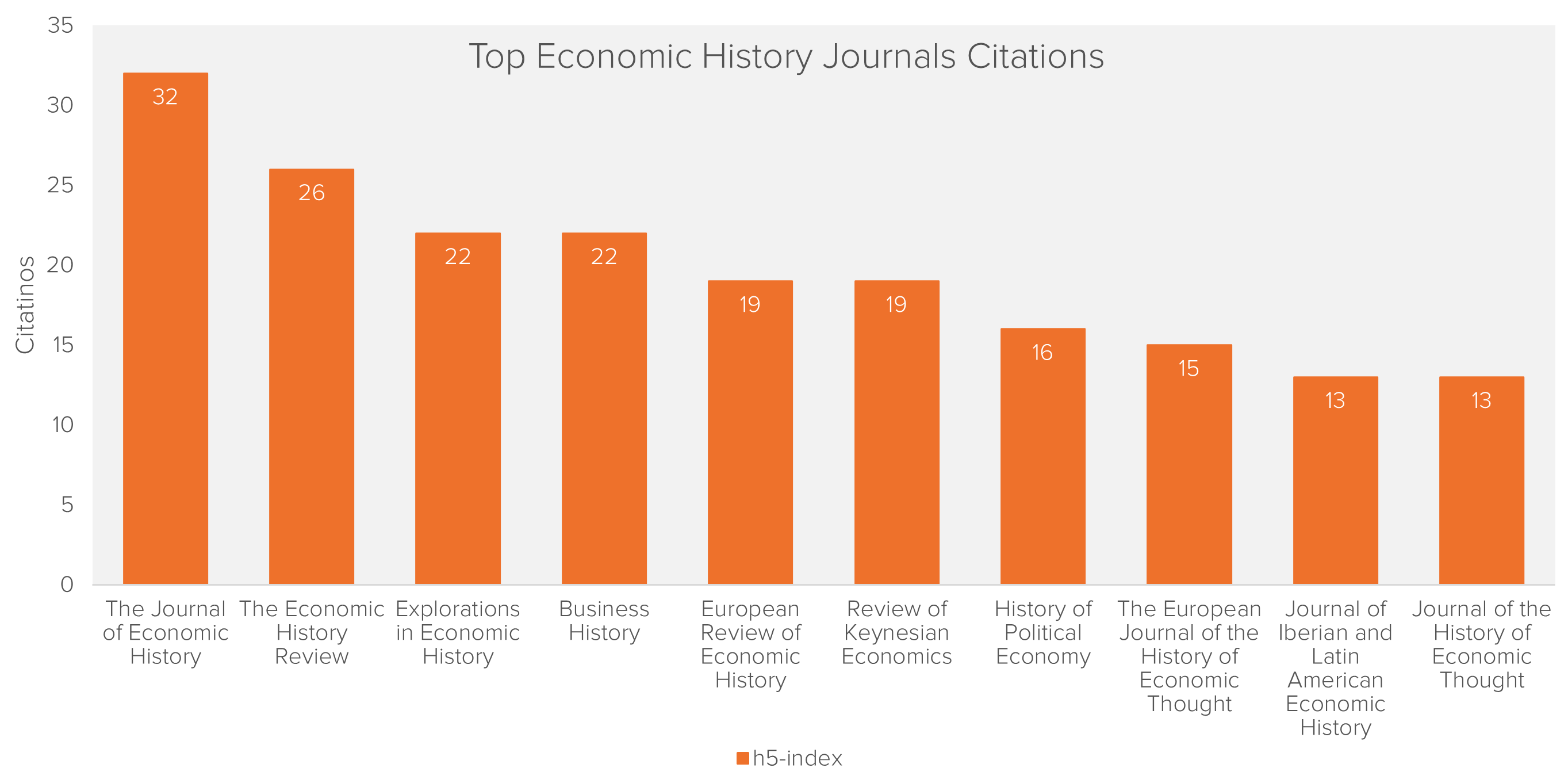

To see the differences in influence and impact of the journals within a likely product market we can look at the extent to which papers published in a journal are cited. Since the network effects are driven by impact, we use this as an indicator of the strength of the network effects that a given journal enjoys. Figure 1 shows an index that measures the impact of leading journals on economic history. It shows that in 5 years The Journal of Economic History (JEH) published 32 papers with at least 32 citations, while the Journal of the History of Economic Thought, published 13 papers with 13 citations. JEH is therefore authors’ first choice to publish in, and a must-have for universities.

Unfortunately, there are clear limits on the ability of a journal to enter and unilaterally set a high-quality offer that can compete against JEH. Unlike a newspaper, a new journal cannot hire the best writers in the hope that this will attract readers (and advertisers). This is because it cannot offer those authors what they want, namely for their research to be stamped with a signal of quality.

This means that the leading journals in each field can have enormous market power. They are highly specialized, and quality differentiated, and hence face just a handful of rivals. They do not need to pay their authors, instead they attract a steady stream of leading research without having to do anything to encourage it, and they can charge readers and libraries supra-competitive prices. This gives them profit margins of 35-40% (compared to 12-15% in magazine publishing). The market power of the leading journals therefore appears uncontroversial. The difficulty is in understanding what, if anything, publishers are doing to maintain that power.

To consider what the dominant incumbents might be doing to exclude their rivals and protect their ability to charge high prices it is worth asking how new rivals might compete to offer a similar signal of quality to authors and readers? One answer is licensing research articles. If a rival could license and reprint the best quality research papers (having assessed those through investing in its own review process), then it could offer readers its take on the leading cutting-edge research in their field, and it could offer authors the signal that their research was worthy of inclusion in a publication with such high standards (alongside other high-quality research by new and established authors). However, at present this is not possible.

Multi-homing by readers is possible (and encouraged by journals), but licensing (or multi-homing) by authors is prohibited. Each journal takes the research that the author has submitted, and in return for publishing it, the journal not only refuses to pay the author anything, but goes further, and requires the author to sign an exclusive copyright clause that prevents any rival paying the author an additional fee to use it either. This prevents the journal’s rivals from accessing the leading research that they know readers want (and which has typically been produced with public funding).

Exclusive dealing of this kind is often unproblematic from a competition perspective. A magazine, a newspaper, or a book publisher will often sign-up authors and negotiate exclusive copyright on the work in question. This allows the publisher to appropriate the full value and hence to pay the author. Many authors agree exclusive deals, taking the view that a single payment for exclusive rights will exceed the payoff from selling multiple non-exclusive licenses to the same content.

However, in book publishing markets we see healthy competition between publishers to sign-up authors on exclusive contracts. Some authors sign for one publisher, others sign for a rival. While there is a race to discover and make a first offer to a new author, if the author considers their options, each publisher (or at least those with good agents) has a chance to make its offer, based on its assessment of the value of the work in question. For this reason, it is not uncommon to see bidding wars erupt between publishers for the work of highly sought-after authors. In contrast, a rival journal publisher cannot compete for exclusive rights. The leading journal has a locked-in advantage that guarantees it first option on any new research in the field (it even prohibits the author from submitting it for parallel review while it decides whether to publish it).

The publisher of a leading journal is therefore able to use its market power to include a clause in the author’s contract that protects its monopoly position. This clause demands exclusive access to the content whilst paying nothing for it. Despite paying nothing, it offers the author no non-exclusive option that would allow the author to multi-home. Instead, it leverages the strength of its network effects to prevent the author selling a second license to a rival journal. This means that we do not see journals compete to attract authors by investing to improve quality. Instead, we see incumbent platforms sweeping up the inputs that an equally efficient rival would require to construct an effective competing product and doing so without the rival having any prospect of outbidding it.

In antitrust, exclusive dealing is assessed under a rule of reason, and can be beneficial. The question is therefore whether this is one of those instances in which it is harmful or not. To find out it is perhaps worth looking at the way that this exclusive dealing framework is reflected in German efforts to persuade research institutions to retain the copyright on the research that their researchers produce (see DICE, 2021). The idea is to enable rival journals to bid for non-exclusive rights to publish leading research and compete with the leading journals. This uses the collective power of research institutions to prevent foreclosure. However, this approach is not available to individual authors and so the market, left to its own devices, has failed to solve these problems.

.

1 In the past the focus has been on the bundling of journals (see Edlin & Rubinfeld) by publishers using the network effects in their leading journals to extract supra-competitive prices for their weaker journals. We also note the potential in the UK and Europe for an exploitative abuse of dominance approach to the issue

Chris joined Fideres in 2021. Chris holds a PhD, an MA and BA in Economics from the University of East Anglia. At Fideres Chris has provided expert economic advice on class action complaints against Amazon, Facebook and Apple. He has written expert reports, developed models to quantify damages, and developed analysis of market definition and abuse of dominance (monopolisation) in digital aftermarkets and multi-sided platforms.

Before joining Fideres, Chris spent 7 years as a Competition Expert for the OECD where he led the economic thinking on antitrust in digital markets, as well the role for competition law in delivering inclusivity. He published numerous papers and led a working party of the OECD Competition Committee in developing new international standards on competitive neutrality and competitive assessment in light of the digitalisation of the economy.

Chris has advised the UK Government’s Department of Trade & Industry on the benefits of competition policy, and the UK Competition Commission (predecessor to the Competition and Markets Authority) on digital mergers, retail market investigations and competition cases. He was an advisor to the Co-operation and Competition Panel on mergers, market studies and antitrust in publicly-funded healthcare markets, and later became Director of Competition Economics at the UK Healthcare Regulator. Chris is a founding member of the Centre for Competition Policy of the University of East Anglia. He remains an associate of the Centre, a member of various advisory boards at non-profit making organisations, and peer reviews papers for the Journal of Competition Law and Economics & the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement.

Another rough ride for financial institutions?

Evidence of collusive behaviour In academic publishing.

Another accounting scandal, made in the UK.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330