Research

New York Taxi Medallions

Another rough ride for financial institutions?

On 2 July 2019, the European Commission (“EC”) published a revised set of guidelines for national courts on how to deal with pass-on in the context of competition claims. In this note, Fideres provides:

The EC previously published a set of draft guidelines on 5 July 2018. While the draft guidelines and the recent publication remain substantively the same, the following points have been expanded and are now explained in greater detail:

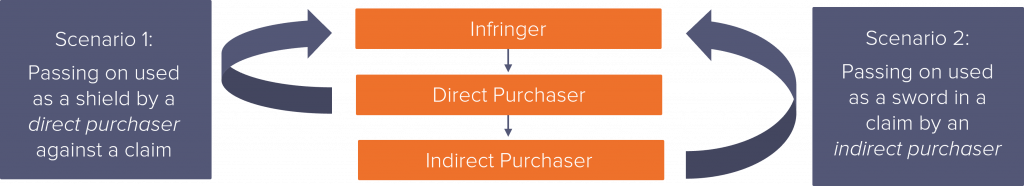

Pass-on is important for the calculation of damages in competition claims. As explained in further detail below, pass-on is used by defendants, to argue that claimants have passed on most or all of the overcharge and therefore are not damaged, as well as by claimants, to show that the overcharge has been passed on to them (in case of indirect claimants) or has not been passed on further downstream (in case of direct claimants).

As per the guidelines, national courts are required to rely on economic analysis and make reasonable assumptions regarding pass-on estimation to avoid both over-compensation and under-compensation to the parties involved.

The difference between the price actually paid, in the presence of anti-competitive conduct, and the price that would have prevailed in the absence of the infringement is referred to as the “overcharge”. When direct purchasers increase their sale prices to indirect purchasers, this behavior constitutes pass-on of overcharges. The total value of sales lost as a result of the direct purchasers increasing prices is known as the “volume effect”.

According to economic theory, the most significant factors that affect the existence and magnitude of pass-on are:

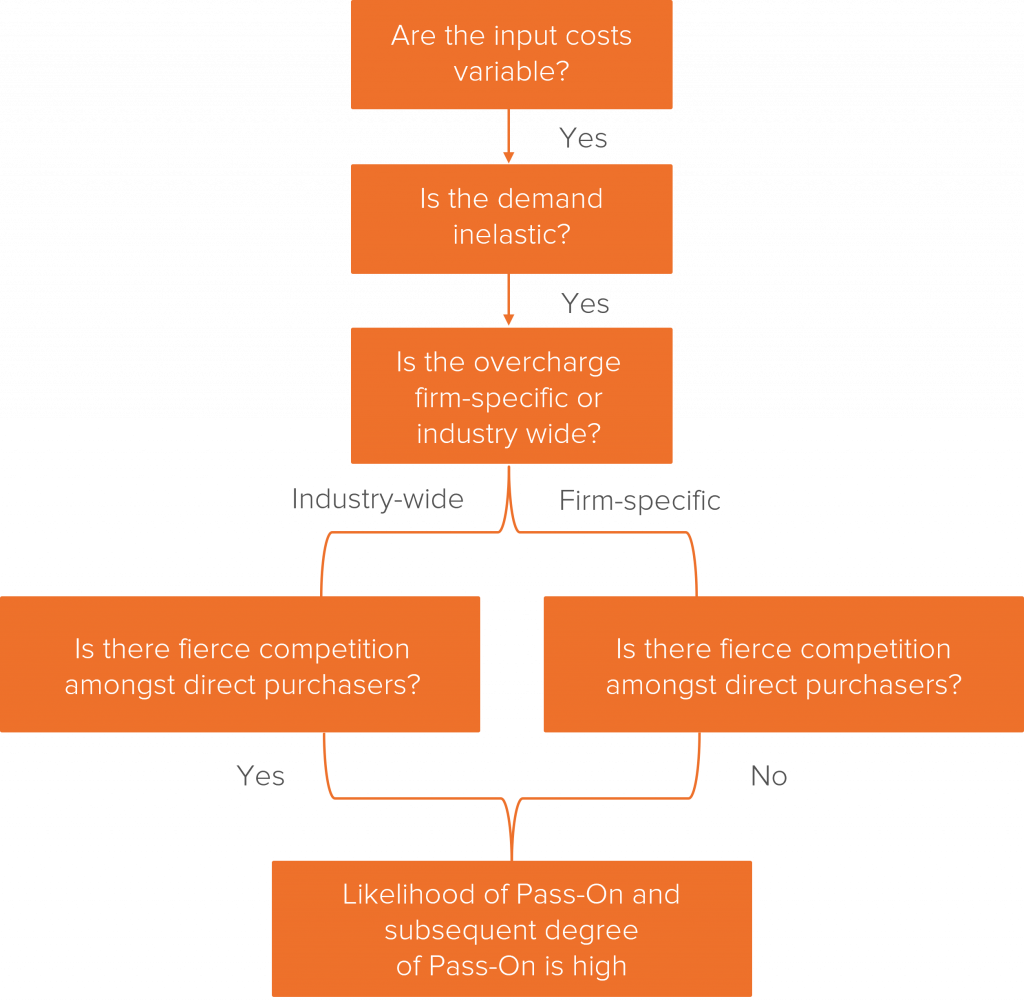

The chart below lists the important markers highlighted by the EC in assessing the degree of pass-on:

There are broadly two scenarios in which national courts deal with pass-on:

According to the EC guidelines, in order to estimate pass-on related price effects, national courts must consider the following two main approaches:

Comparator-based methods involve analysing the prices set by the direct purchaser during the infringement period and the prices set in similar markets. Qualitative evidence such as internal documents that reveal key information about pricing decisions may also be relevant, but in terms of quantitative evidence, the EC has identified that regression analysis is the best technique for courts to rely on.

The different approaches to determine but-for prices under comparator-based methods are outlined below:

| Cross-sectional (1) | Time Series (2) | Difference-in-difference (3) |

| Analaysis of the same product market but in a: | Analysis of the product market before, during and/or after the infringement | A combination of (1) and (2) |

| - different geographical area, or | ||

| - another product market that is considered to function in a similar way to the market in which the direct/indirect purchaser operates |

The passing-on rate approach involves analysing how previous changes in a firm’s costs have affected prices before or after the infringement period. For instance, the passing-on rate may be estimated by analysing how historical changes in the cost of copper have affected the price of wire harnesses. If an increase in the cost of copper by GBP 10 is followed by a price increase of wire harnesses by GBP 5, this constitutes a pass-on rate of 50% to the car manufacturer.

The volume effect represents the lost volume due to an increase in price set by the direct purchaser. Volume effect is estimated by considering:

In Cheminova (2015), the expert estimated the volume effect as a product of the counterfactual margin and the lost quantity of products sold due to pass-on. Sales in this case were calculated based on a market price elasticity estimate along with the observed prices and quantities.

In general, many of the methods mentioned above are feasible only if they are “proportionate” to implement. When assessing proportionality of an order to disclose information, the court must consider choice of economic method and approach as per the guidelines. For example, what may be proportionate for a EUR 20m claim may not be the same for a EUR 200,000 claim. One of the main challenges that experts face is the lack of reliable data, especially at an early stage (i.e. pre-disclosure).

To understand the future scope of a claim, practitioners must use publicly available information, which is often limited, to arrive at a reasonable overcharge or pass-on estimate, before decided whether it is worthwhile to pursue a claim.

We discuss two possible alternative approaches in the following section.

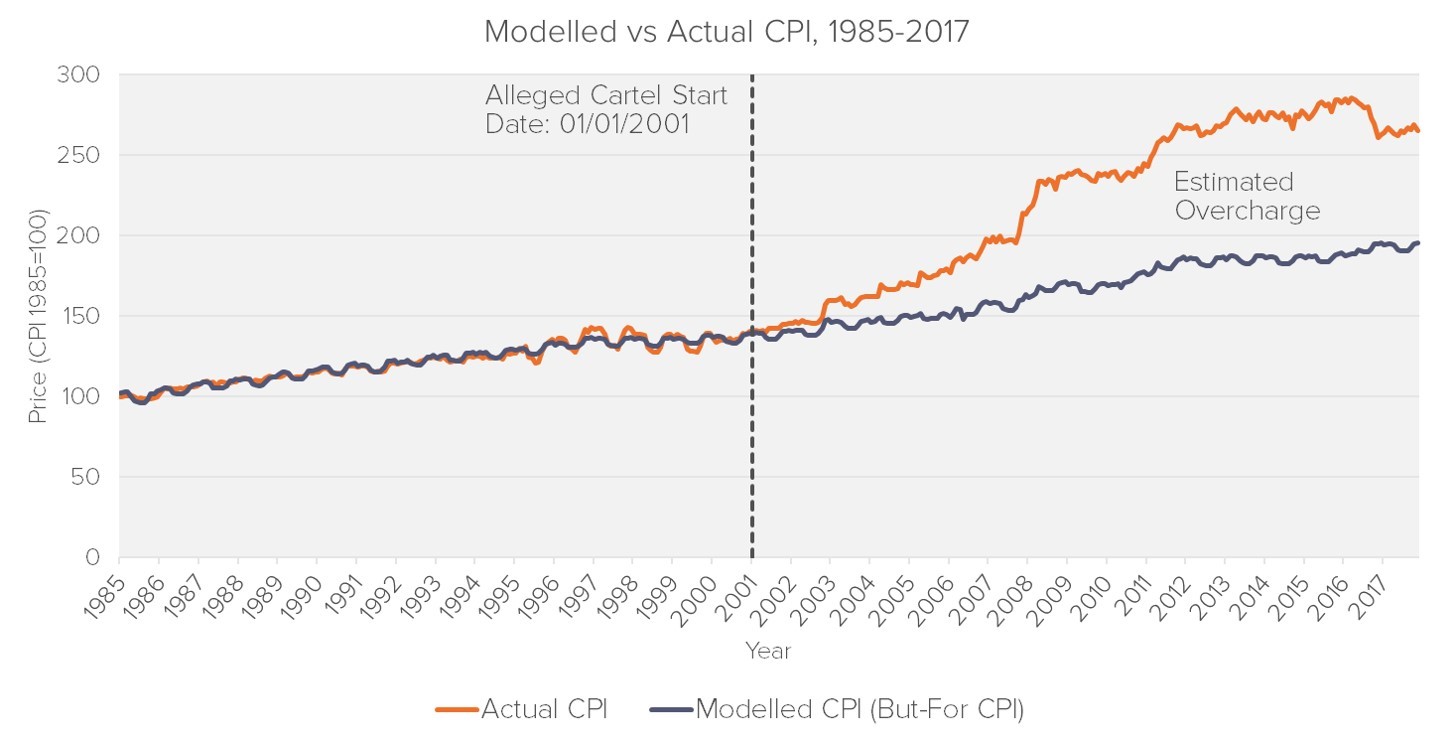

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”), the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) measures the changes in prices paid by consumers. The Producer Price Index (“PPI”) measures the average change in selling prices received by producers. Using national CPI and PPI data, we can estimate but-for prices and pass-on rates for retail or producer markets. Naturally, producer prices are a good indicator of retail prices within the same market. Similarly, producer raw material costs are a good indicator of producer prices.

By mapping within-nation CPI and PPI data, we use regression analysis to predict but-for prices that would have otherwise been paid by indirect consumers to the direct purchaser (“But-For” CPI) by accounting for the cartelised input cost (PPI). We can then estimate these model parameters to ascertain pass-on in different sectors and sub-sectors of product categories, according to levels of the supply chain that were affected. To bolster the standardized regression model, we can also add market-specific demand, supply and structural factors to create a sophisticated but-for model. Examples include quantities demanded and supplied; imports and exports; exchange rates; raw material costs; prices of substitutes and inflation.

On 31 October 2017, the Canadian competition authorities publicly announced that they were investigating seven bread suppliers and retailers for price fixing. A separate application for class certification and damages, on behalf of consumers for bread and related products, was also lodged in an Ontario court on 21 December 2017. Using this ongoing case as an example, we illustrate how our standardised model can be used to estimate but-for prices:

We can track changes in CPI due to changes in indirect taxes such as Value Added Tax (“VAT”). Economic literature suggest that firms generally increase prices in response to VAT increases, in order to pass on the incidence of the tax to the consumers.

In order to estimate pass-on in a given product category, Fideres has assessed the following key variables:

Certain pitfalls, however, make this type of analysis more complex that it might appear at first glance. These include:

Pass-on can be difficult to quantify, mainly due to high data requirements. The alternative approaches discussed in this note can be useful because:

They are based on regression techniques, which, according to the EC, are best suited to provide reliable quantitative but-for prices, in the context of antitrust legal disputes.

Russell joined Fideres in 2014. He has acted as a consulting expert in many large legal cases in the US and UK for a variety of industries. In particular, he leads the pharmaceutical antitrust team in relation to generic drug price-fixing allegations, labour economics team in relation to wage suppression and has carried out expert work in financial markets claims involving swap mis-selling and fund management excess fees. Russell is a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) charter holder and completed his BSc in Accounting and Finance at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Another rough ride for financial institutions?

Still navigating in troubled waters?

The role of pharmacy benefit managers In US drug pricing.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330