Research

Goodwill Hunting

How forced bank bail-outs in early 2023 have resulted in fantastic gains for the acquirers.

During approximately two weeks in Autumn 2018, about half a million air travelers typed their personal and financial information – names, addresses, email accounts, credit card numbers – into the BA website to make bookings. Unbeknownst to them, a script maliciously planted on the BA’s server quietly “skimmed” this information and forwarded it to a group of unknown hackers.1

The ICO blamed this break on BA’s “poor security arrangements.”2 The airline now faces the largest-ever fine in history of the ICO, and the first-ever fine to be imposed under the new GDPR regulatory regime. This fine may signal the start of a new era for regulatory actions and private claims concerning data breaches in the UK and EU.

Since the implementation of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR3) in March 2018, the ICO has reported more than 14,000 individual notifications of data breaches, more than four times the number reported in the year preceding the GDPR’s implementation.4

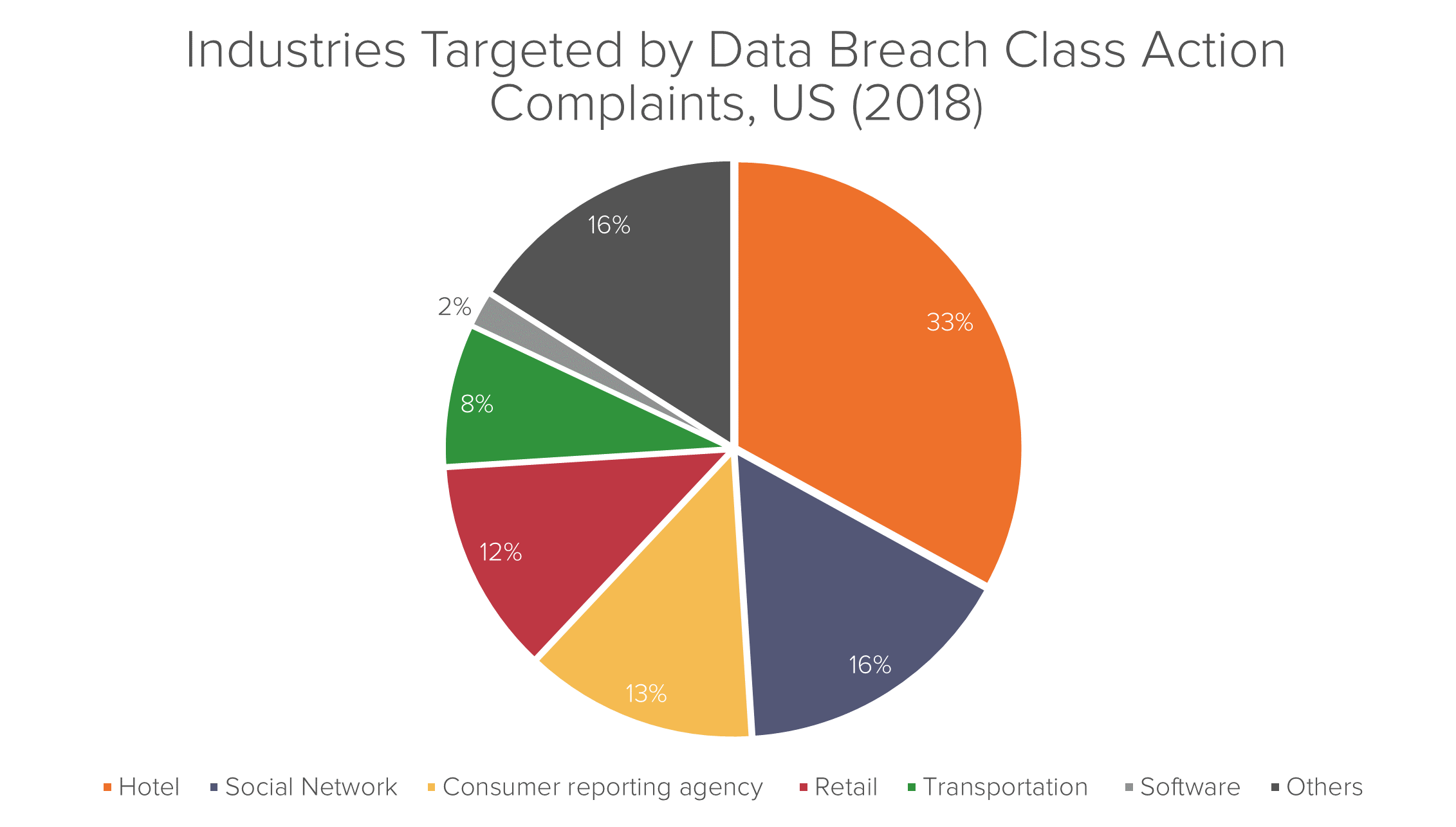

Meanwhile, data breach class actions against companies are a large and fast-growing area for consumer litigation in the US. More than a hundred class actions related to data breaches were filed in 2018,5 but these covered only about 7% of all publicly reported data breaches.6

The range of organizations which have failed to protect sensitive personal data is remarkably wide. Breaches have been reported both by ostensible digital natives such as Facebook and Twitter, as well as the stalwarts of more traditional industries, such as transportation and retail.7

Despite businesses’ increasingly sub-par performance in protecting privacy rights in Europe and the US, possible frameworks for litigation on behalf of the victims remain relatively under-explored in both jurisdictions.

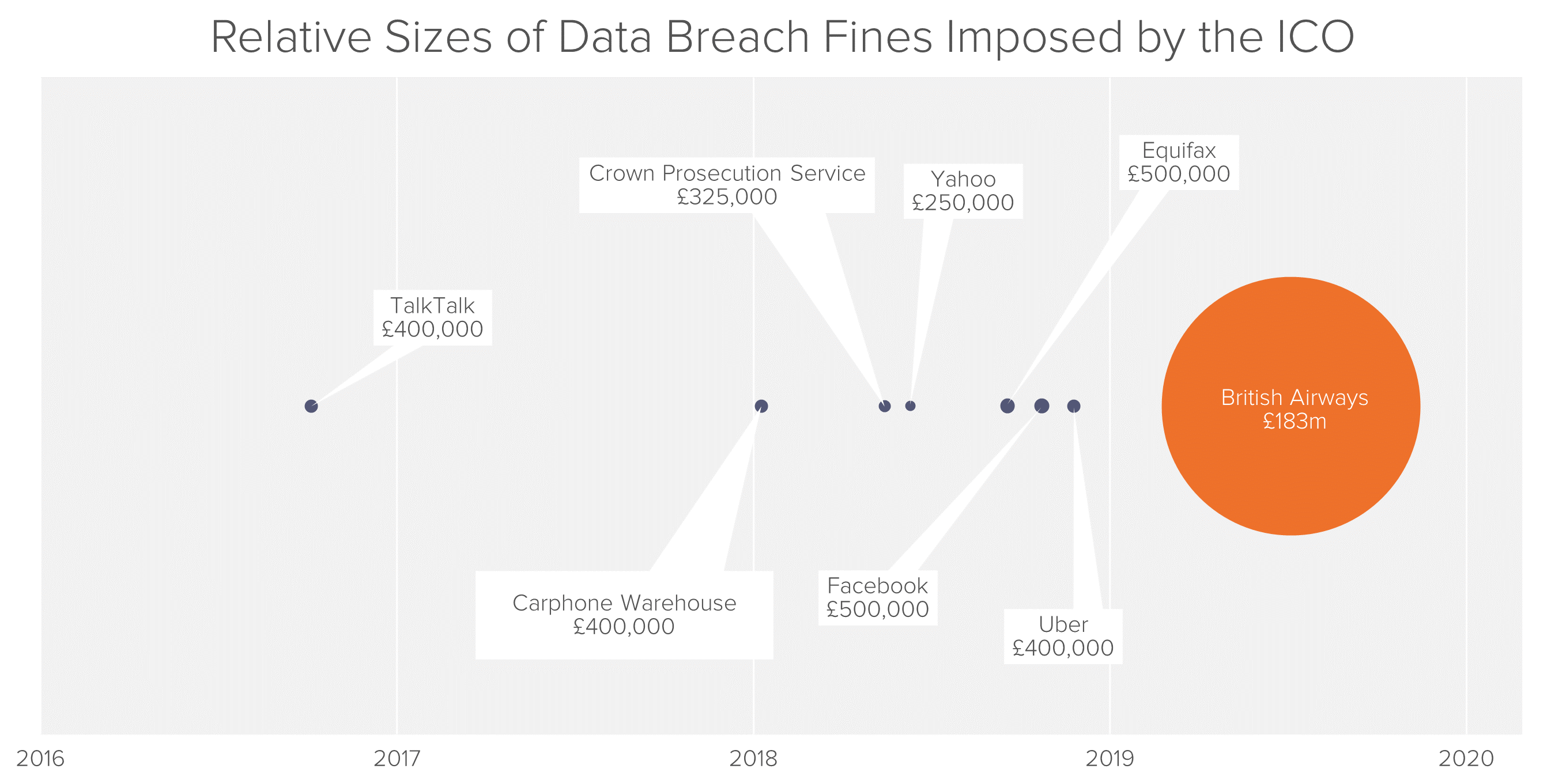

In Europe, where public action can serve as a de facto prerequisite to private litigation, regulators have proceeded cautiously. The ICO had issued a number of minor fines related to data breaches, but until the announcement of the sanction against BA, none had exceeded the pre-GDPR ceiling of £500,000 prescribed by the UK’s Data Protection Act 1998.

Nevertheless, the new regime could have profound implications in the long term.8 According to Ross McKean, a partner at DLA Piper specializing in cyber and data protection, GDPR changes the compliance risk for organizations that suffer a personal data breach, as potential consequences now include fines based on company revenue and the possible prospect of class action litigation. The GDPR allows fines up to £20 million, or 4% of a company’s annual turnover for regulatory infringements related to data breaches. The $183m fine against BA, although it dwarfs the ICO’s previous data breach fines, amounts to only around 1.5% of the company’s annual turnover, or less than half the potential maximum.

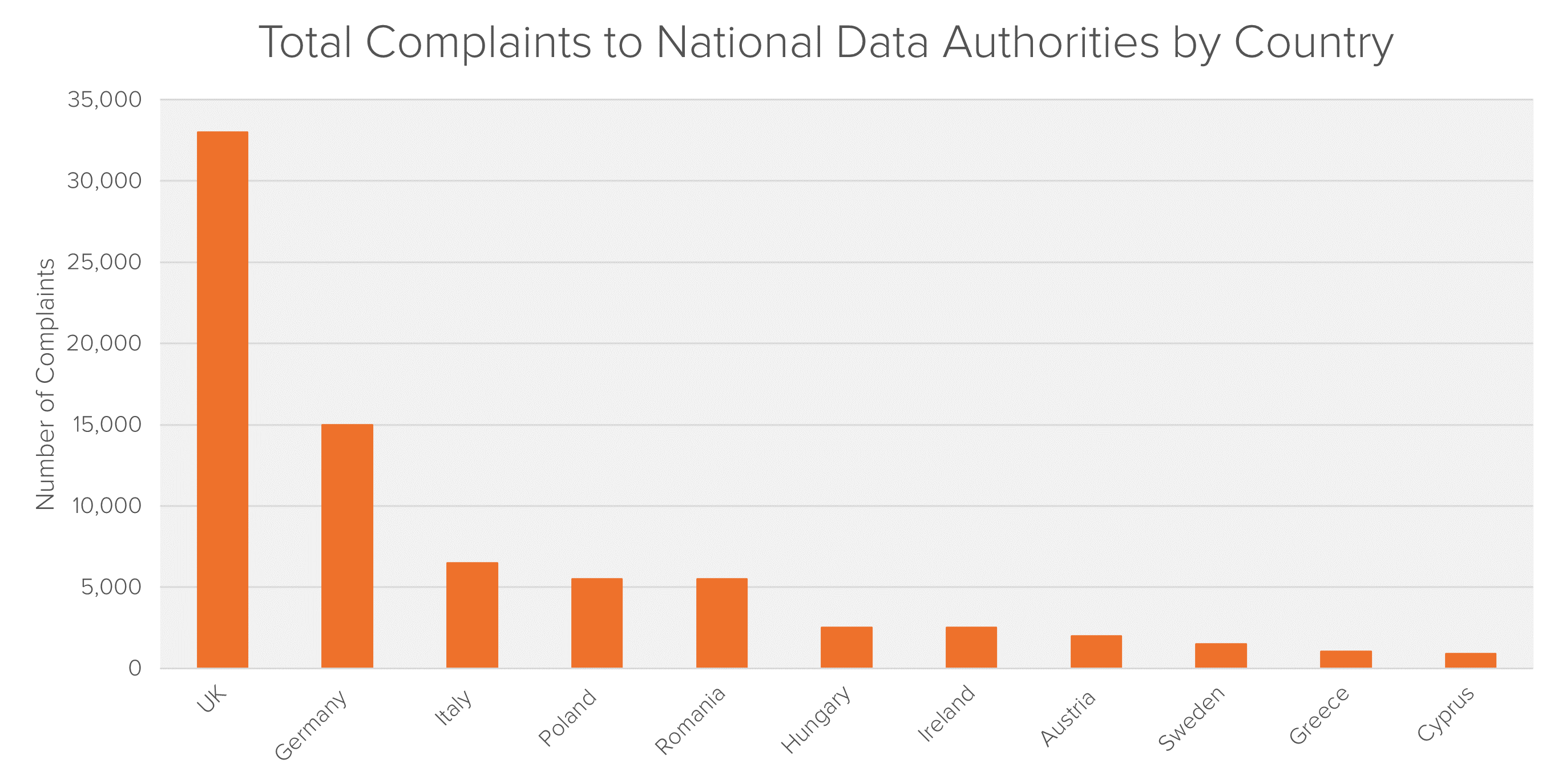

In an environment of bolder private data breach litigation, the UK is likely to be one of the most promising venues. Not only have the fines against BA signaled a willingness by UK regulators to deploy the new rules, the ICO’s data also shows that it receives more complaints than any other European country’s data protection regulatory by a significant margin.9

Of all class action suits related to data breaches filed in the United States, only four had reached a decision on class certification by the start of 2019.10 Most cases failed to progress past the motion-to-dismiss stage, either failing to show the cognizable injury required to invoke the authority of a federal court (“Article III” standing) or failing to demonstrate that issues common to the class predominated over individual concerns.

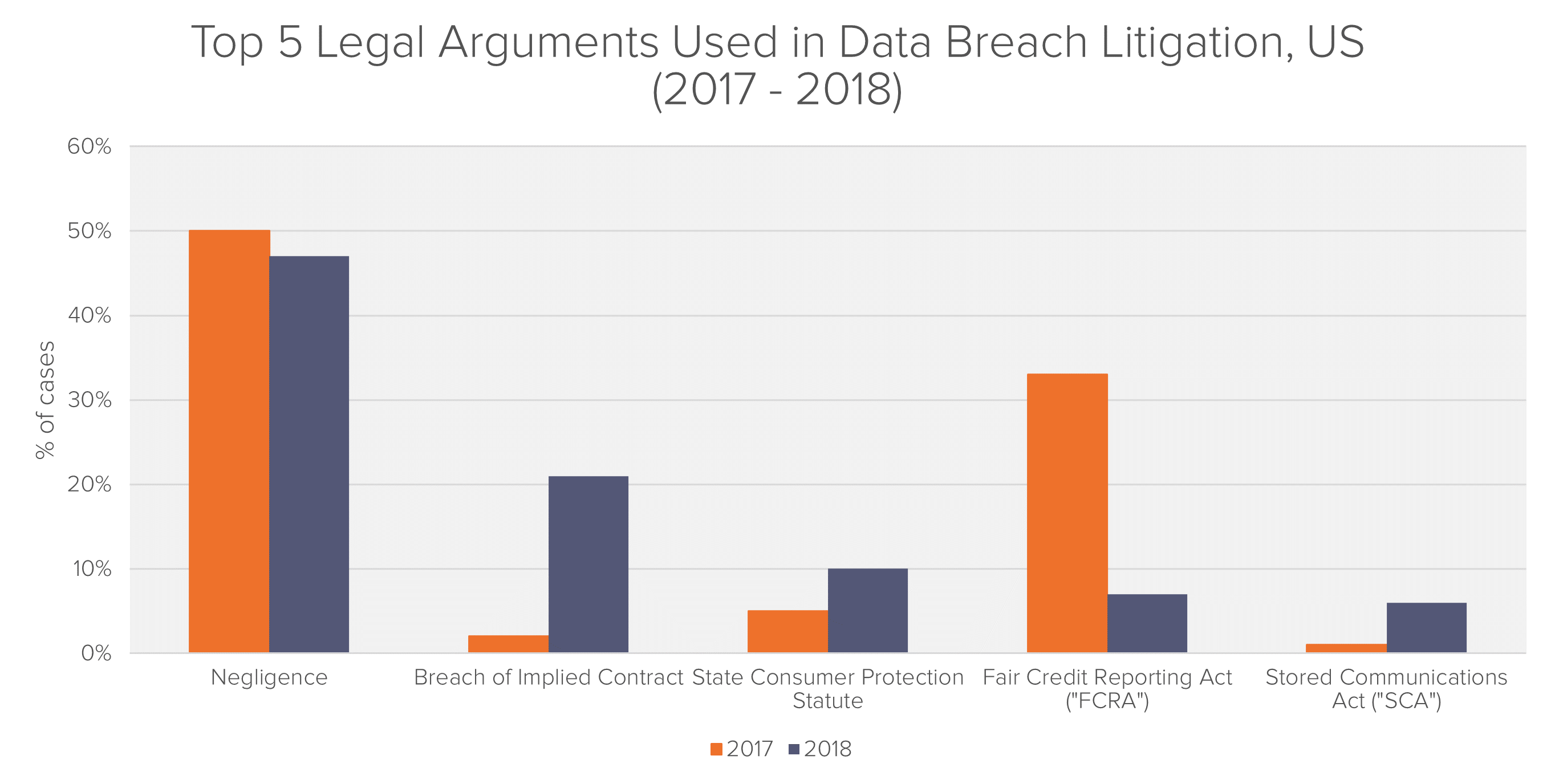

The legal and economic approaches taken in these cases have been diverse, as plaintiffs test how receptive the courts are to different arguments. Besides reflecting the United States’ entrepreneurial approach to litigation, the variety of actions in this jurisdiction arise from the lack of a unified GDPR-like framework. In both 2017 and 2018, almost all plaintiffs chose to allege more than one theory of recovery, with plaintiffs’ attorneys alleging an average of 4 to 5 theories per complaint.

Although data breach litigation is relatively new and the landscape is still shifting, the key economic difficulties that are emerging in both the academic literature and the courts are questions around the common nature of the harm and the quantification of the damage.

In many cases in the UK, damages have been awarded for psychiatric and psychological distress as a guide to the appropriate level of damages to be awarded to each victim. For example, the High Court awarded damages of up to £12,500 each to six individuals as compensation for the “shock and distress” caused to them by the accidental publication of their personal data by the Home Office.12

Perhaps the simplest conceptual approach to analyzing harm is monetary losses directly resulting from the misuse of stolen personal information; for example, fraudulent credit card purchases which would not have taken place but-for the breach.

This approach is however unlikely to be suitable for collective actions, as any ensuing damages analysis would require a number of plaintiff-specific inquiries. Any aggregate or average estimate based on the named plaintiffs’ claims – or on some source of information not specific to the proposed class – would inaccurately measure charges experienced by individual class members. As a result, class certification under Rule 23(b) could be problematic.

Another key hurdle with this approach lies in the legal requirements on alleging harm when this has not yet directly occurred. In Clapper v. Amnesty International, the US Supreme Court set a precedent, compelling plaintiffs to show harm to be “certainly impending” as opposed to “objectively reasonably likely”. While this case was unrelated to data breach, and the Supreme Court has to date never directly ruled on any such cases, this has nevertheless become a touchstone for data breach litigation.

In the Adobe data breach case in the United States, the judge ruled that the sheer amount of effort that had been put into the hacking effort was sufficient evidence that the certainty of impending harm could be reasonably inferred. In other cases, in which a company or organization’s negligence has allowed for a crime of opportunity and there is little certainty that all the stolen or compromised data will be used, this requirement might be more prohibitive.

A slightly more indirect theory supposes that consumers incur harm through lost time spent mitigating the effects of a breach. These include activities such as freezing accounts, setting up alerts with credit reporting agencies, and monitoring credit reports. For example, in the Target Settlement, class members were deemed to be eligible for two hours of time lost for $10 per hour for each type of documented loss they incurred.

As with the direct harm approach, the challenge with claims of this nature is that it is difficult to ascertain time spent only on these activities. Even if it were possible, the value of a class member’s time is of course inherently individualized. In the Target case – one of the largest breaches in history, involving more than 41 million people – a plaintiff class using this theory of harm settled with the defendant for $18.5 million.

Damage theories relating to the “benefit of the bargain” argue that there is a “data security premium” built into prices of products sold by the breached entity. As a result, in data breaches caused by the negligence of the defendants, consumers either paid that premium under false pretense, or would have avoided firms with weak IT systems altogether.

For example, the plaintiffs in Neiman Marcus argued that they overpaid for the products because the store failed to implement adequate security system. The defendants settled for a total amount of $1.6m.13

The economic challenge in this case lies in the quantification of the “secure data premium”. Many data breaches involve companies that charge consumers nothing at the point of service, such as Facebook.

The problem of “commonality” is pervasive in group legal actions, and the theories of harm in data breaches do not escape it. In any given incident, not every class member’s data has the same value, and not every class member values their privacy in the same way.

One way of at least quantifying this heterogeneity, if not avoiding it, is to put the question directly to the class members themselves. There exist statistically valid sampling techniques that allow subsets of the class to provide insight into the views of the whole. A scientific survey could be used to determine, to an arbitrary level of statistical confidence, the extent of the variation between class members in their subjective valuations of damages.

Each of the conventional approaches discussed in the previous section share one principle: they quantify harm through the subjective value that victims place on their data. An alternative might be to examine the value of the data from the perspective of a potential buyer.

Indeed, an empirical source of information on the value of individual consumer data is the market itself. A survey or analysis of the appropriate websites could be used to estimate the average price that hackers and scammers are able to obtain for information like phone numbers, email addresses and social security numbers. The information that was compromised in the data breach could be valued in cash terms according to which pieces of information were stolen and the prices generally obtained for those pieces of information.

Although consumers may place more or less value on their personal data than this price reflects, this is a more general economic problem, and is not unique to digital information. Suitable theoretical justification for a “market price” theory of damages can be found in any group damages calculation that arrives at a class-wide damages number by calculating sales times price.

Following the data breach, BA sent an email to affected customers notifying them of what personal data had been stolen. In the email, the company also offered a free 12-month membership to Experian ProtectMyID, a service which is designed to help “detect possible misuse of […] personal data and provides […] identity monitoring support, focused on the identification and resolution of identity theft”.

In addition to Experian ProtectMyID there are other identity protection service such as LifeLock and IdentiyForce. Most of these services offer tiered plans ranging from $9 per month to $25 per month.

Since BA offered a one-year subscription to affected customers for their “assurance” one might consider the value of this product as a floor or a starting point when it comes to damages estimation. In a functioning market for these services, the competitive price for this assurance can be no greater than the dollar value consumers put on spending the time and effort to do such monitoring themselves. As such, the cost of the subscription services might serve as an easily quantifiable baseline for the value of the “time lost” in mitigating a breach, as discussed in the Target settlement.

Viewed another way, one might argue that customers who wanted to book flights through the BA website but were concerned about the company’s cyber security would at least want such an identity protection service, so that in the event of a leak, a hacker could not exploit it. In this scenario, the price of these products would again serve as a floor for potential damages estimates.

1 https://techcrunch.com/2018/11/13/magecart-hackers-persistent-credit-card-skimmer-groups/

3 Post-Brexit, the GDPR’s provisions in the UK will be mirrored and reimplemented at the nation level by the UK Data Protection Act 2018

5 Data Breach Litigation Report 2019: Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP

6 Data Breach Litigation Report 2019: Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP

7 Data Breach Litigation Report 2019: Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP

8 https://www.dlapiper.com/en/ukraine/news/2019/02/dla-piper-gdpr-data-breach-survey/

9 https://fideres.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/25-March-2019-GDPR-Today_GDPR-in-Numbers.pdf

11 Bloomberg BNA: Privacy and Security Law Report

Max joined Fideres in 2016. He has led the development and implementation of economic models for major collective actions in the US and the UK, contributing to litigation on a variety of topics. His reports and econometric work has been included in cases for conduct including, among others, the FX and LIBOR benchmark manipulation, digital market monopolisation by Apple and Amazon, and consumer claims against a cartel of US generic drug manufacturers, abuse of market power by large regional US hospital systems, restriction of the right to repair by John Deere, and the combined abuse of dominance by Visa and Mastercard in UK payment systems. Before joining Fideres, Max worked at the national laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, as part of a team designing neural networks for applications in machine learning. Max holds an MSc in Economic History from the London School of Economics.

How forced bank bail-outs in early 2023 have resulted in fantastic gains for the acquirers.

Issues with Fund Valuations may yield to future litigation.

Arbitration clauses limit consumers’ ability to pursue collective actions.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330