Research

European Trucks Cartel

A preliminary damages model.

In 2018, the Payment System Regulator (“PSR”) launched a cartel investigation against five prepaid card networks: Mastercard, Allpay, APS, PFS (now EML) and Sulion.1

On 31 March 2021, the PSR announced an aggregate fine of £32 million against Mastercard, Allpay and EML, who admitted the charges of market allocation. The press release2 specifies that the anticompetitive conduct affected the services provided to local authorities in the UK.

Councils typically award annual or multi-annual contracts to prepaid programme operators under public tenders. An analysis of the government public tenders database3 has produced the following information in relation to prepaid contracts:

Since at least 20114, local authorities have been using prepaid cards for the payment of select types of benefits to council residents. After the implementation of Universal Credit5 in 2018, there are two main types of benefits that fall under the remit of local authorities: housing benefits (with the exception of those comprised under Universal Credit) and social care benefits (disability allowance, carer allowance and others).

Prepaid cards are seen as the solution to some of the challenges faced by councils. Councils often mention the following benefits of prepaid cards:

Prepaid card programmes are rolled out through public procurement tenders, published on the government tenders portal. Over time, a number of local authorities have joined framework agreement schemes, in order to centralise a number of administrative functions such as the negotiating, setting up and ongoing monitoring of arrangements with prepaid card providers (examples include the North East Purchasing Organisation prepaid cards framework agreement and the Surrey County Council Framework Agreement). Organisations such as the National Prepaid Cards Network also provide guidance and support on how to prepare and run the tender process for the roll-out of prepaid card schemes.

To the extent that market allocation occurred, as alleged by the PSR, limited or no competition would occur and we expect to see tenders being awarded at the upper end of the pricing range of the estimated value of the contract as specified by the local authority in the tender document.

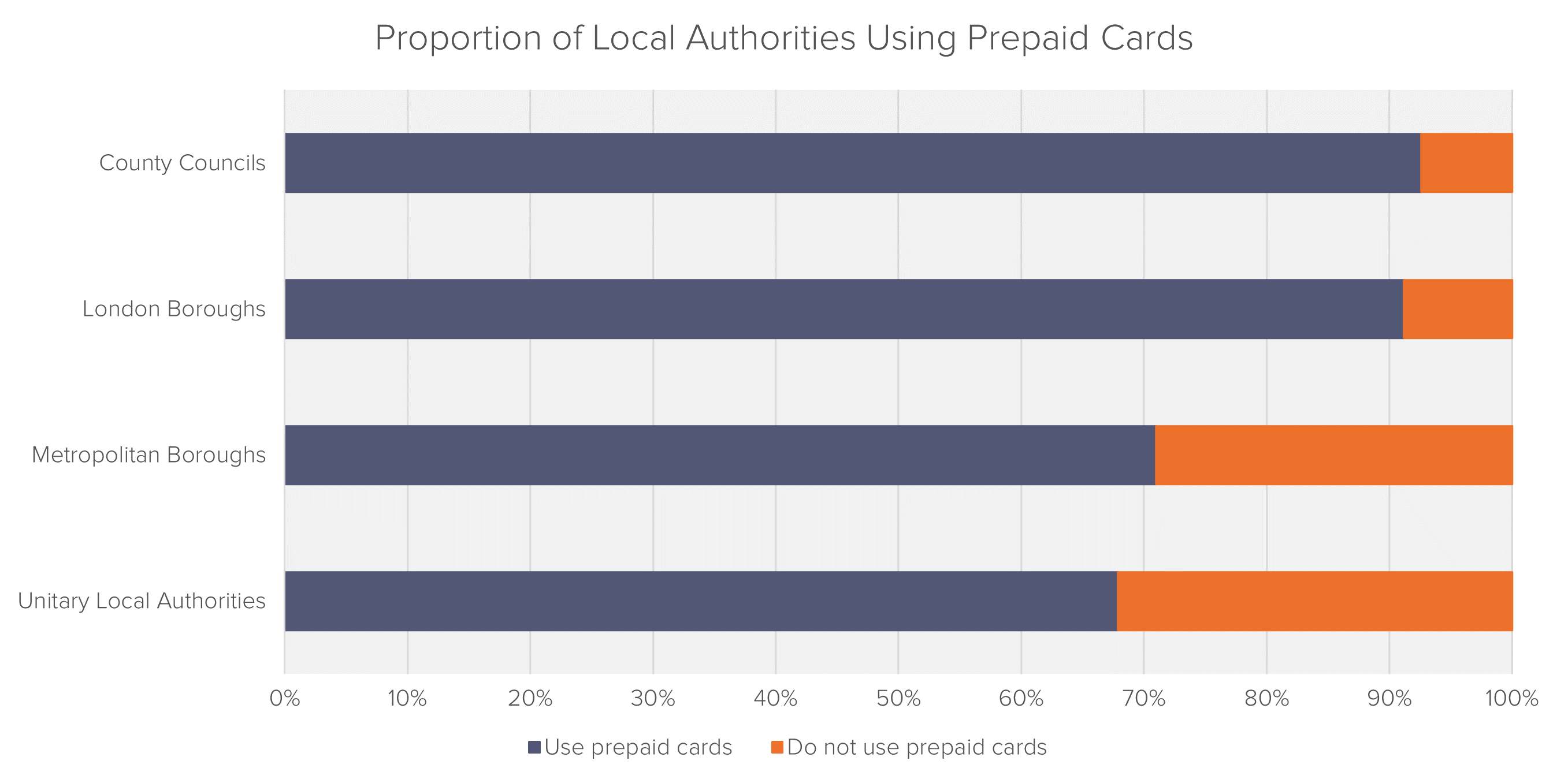

According to the National Prepaid Cards Network, as of August 2018 over 130 councils (out of a total of 152 Councils with Adult Social Services Responsibilities9 10), 20 Clinical Commissioning Groups and 12 housing associations used prepaid cards to deliver direct payments and other services.11 EML also provides a list of local authorities using prepaid card schemes.12

Based on figures provided by the National Prepaid Cards Network13, we have estimated the aggregate amounts uploaded on prepaid cards at approximately £2.2-2.5bn.

Councils use prepaid cards for a variety of purposes, both in their capacity as agency and employer.

Prepaid cards are used for making direct payments to customers for a variety of reasons:

Councils can also use prepaid cards to replace traditional payment methods in its role as an employer in applications such as:

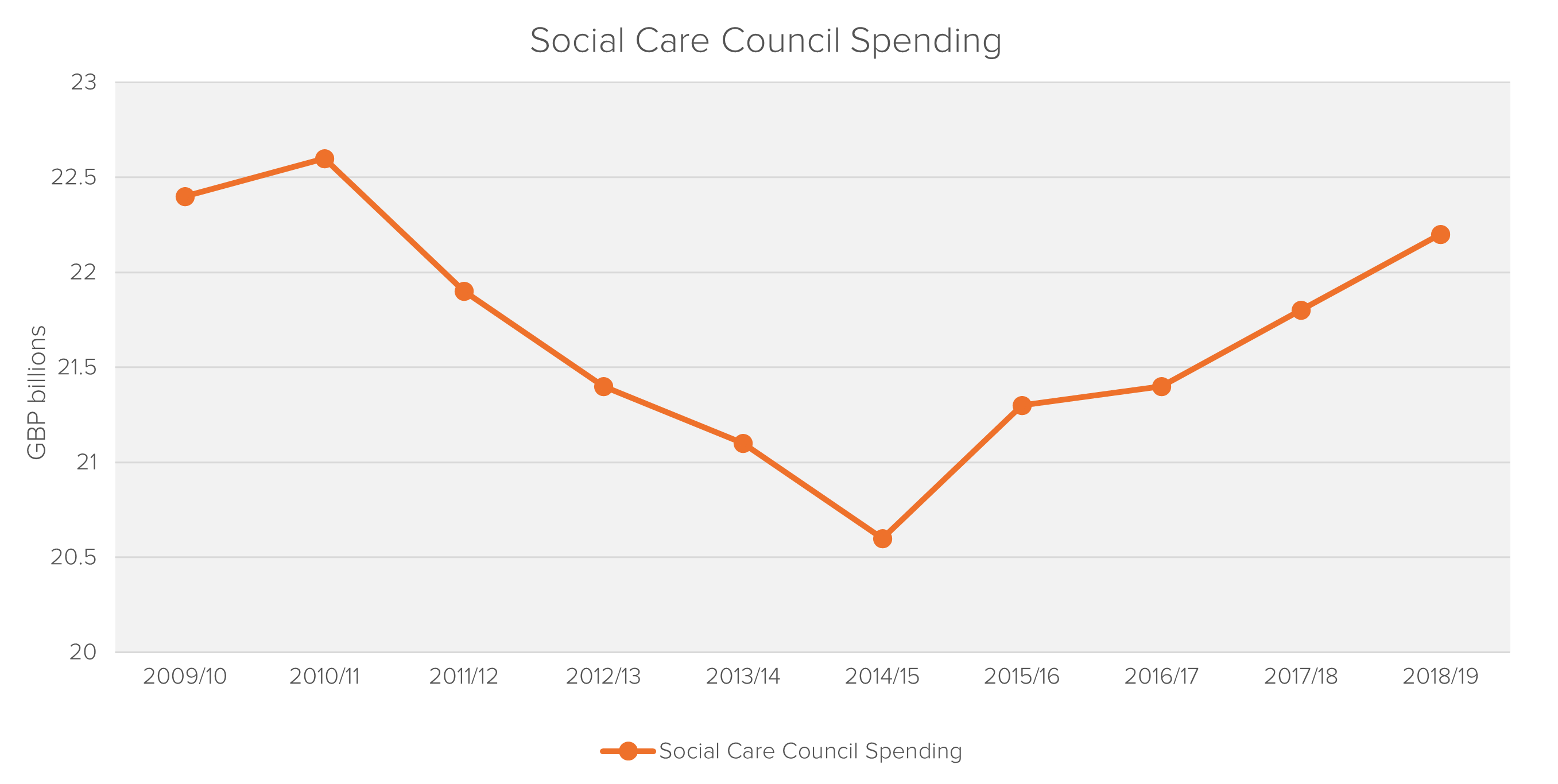

The chart below shows the historical evolution of social care spending:

Social care encompasses adult social care and children’s social care, representing the largest proportion of local authority service expenditure. In the 2018/19 fiscal year, adult care was approximately 17% of the English councils’ budget – £16bn– and children’s care made up about 9% of councils’ budget, or £8.5bn.15

A 2017 study16 submitted freedom of information requests to all UK local authorities with social care budget responsibility, in order to assess the use of prepaid cards. They found that 15% of social care payments were made by prepaid cards.

During the 2017 study, pre-paid cards were used in an estimated 69 of the 152 authorities surveyed, or 46% of the total. Fideres’s research shows that today, the proportion has increased to 78%: 116 out of 148 authorities make use of prepaid cards.

Within these authorities, according to the Local Government Association17, approximately 28% receive direct payments for social care or approximately 106,000 people, according to the latest report.

Based on an estimate of 15% of people who receive direct payments via prepaid cards18 and an annual social care spending figure of approximately £20bn, the amount of funds uploaded onto prepaid cards annually is in the region of £2.3bn.

Fideres has filtered publicly available sources of council tenders19. Over the period from January 2015 to now, UK local authorities have awarded contracts to prepaid card networks with an aggregate value of approximately £36 million.

The data shows that PFS won 76% of all tenders for prepaid card services run by local authorities since 2015, Allpay won 23%, and the remaining contracts were awarded to APS. Although there could be other contracts not subject to public tender, these figures give us an indication of why PFS and Allpay appear to have settled the charges levied against them by the PSR.

The table below provides a breakdown of the prepaid contracts awarded by tender over the past twelve months, according to bidstats a search engine for UK public sector contracts.20

| Contracts Awarded Last 12 Months | PFS | Allpay |

| Number Contracts Awarded | 10 | 45 |

| Total Award | £ 2,327,000 | £ 56,507,000 |

| Max Award | £ 800,000 | £ 33,000,000 |

| Min Award | £ 32,000 | £ 23,000 |

| Average Award | £ 232,700 | £ 1,255,711 |

The market allocation conduct admitted by the prepaid card providers has likely caused anticompetitive injury to both councils and consumers.

Councils incur fixed (one-off) and variable (ongoing) charges for the set-up and running of prepaid schemes. Typical charges21 include:

| Type of Fee | Estimate provided by Mastercard via Prepaid Network |

| Set up fee | £0 - £1000 |

| Annual fee per card | £0 - £36 |

| Card issue | £2 - £4.95 |

| Additional card for a single account | £2 - £4.95 |

| Inactive card | £0 - £4.95 |

| Replacement of lost card | £2 - £4.95 |

| Point of sale/online transaction fee - UK | Free to client |

| ATM use - UK | £0.99 - £1.00 |

| Standing orders and direct debits | £0.35 - £1.50 |

| Bounce back | £20 |

| BACS transfer | £0.35 - £0.50 |

| Merchant blocking | £500 - £1000 |

| Cancellation of card | £10 |

| Load | £1 or 1.5% per load, often free as part of monthly charge |

| Claw back | Free |

Therefore, damages to local authorities may result as a combination of: (a) inflated set-up costs and (b) excessive running costs (e.g. load costs, BACS transfer costs etc).

Based on the figures we have gathered, we estimate the total spending over six years across the 116 local authorities using prepaid cards as below:

| Type of Fee | Total spending |

| Scheme set-up | £116,000 |

| Annual fee per card (over 6 years) | £17,860,000 |

| Card issue (one-off) | £409,000 |

| Load fees (over 6 years) | £6,000,000 |

| Total | £24,385,000 |

As a result, damages are probably too low to make a private enforcement action viable in the English courts.

3 https://www.gov.uk/contracts-finder

4 Guide-to-the-use-of-Prepaid-Cards-2nd-edition.pdf (prepaidnetwork.org.uk) p.16

5 As defined by the UK government “Universal Credit is a payment for people over 18 but under State Pension age who are on a low income or out of work. It includes support for the cost of housing, children and childcare, and financial support for people with disabilities, carers and people too ill to work”.

6 Councils’ use of prepayment cards risks contravening Care Act, study claims (communitycare.co.uk)

7 Ibid

8 Prepaid cards (southampton.gov.uk)

10 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmhealth/22/2205.htm#n12

11 https://prepaidnetwork.org.uk/

12 https://prepaidfinancialservices.com/en/councils

13 Presentation dated August 2018 by the CEO of the Network presents a figure of GBP312m for the first five months of the 2018/19 financial year. We used this figure to extrapolate the amount of funds uploaded.

14 Prepaid Financial Cards – Adult social care.pdf (manchester.gov.uk)

15 Local Authority Revenue Expenditure and Financing 2019-20 Budget England Link

16 “Payment Cards in Adult Social Care, A National Overview 2017”, researched and written by In Control and published by Shaw Trust on behalf of Living Strategy Group.

17 https://lginform.local.gov.uk/

18 “Payment Cards in Adult Social Care, A National Overview 2017”, researched and written by In Control and published by Shaw Trust on behalf of Living Strategy Group.

19 https://www.contractsfinder.service.gov.uk/

20 bidstats – UK Public Sector Contracts

21 Based on an official Allpay document, disclosed by the UK Government: https://www.digitalmarketplace.service.gov.uk/g-cloud/services/382806147391897 under Pricing Document and also: https://prepaidnetwork.org.uk/web-cont1001/uploads/Guide-to-the-use-of-Prepaid-Cards-2nd-edition.pdf , page 11

See also: Prepaid cards: best UK offers for 2021 – MoneySavingExpert

In 2009, Alberto co-founded Fideres. As a partner, Alberto has mainly focused on developing market analyses and novel methodologies aimed at identifying anomalous or illicit behaviors such as: market manipulation, benchmark fixing manipulation, product mis-selling, anti-competitive conduct and discrimination conduct.

Since 2014 Alberto is the managing partner of Fideres Inc USA, Fideres’s US arm. Alberto has acted in an expert witness capacity in disputes involving banks and brokers, on one side, and institutional investors or consumers, on the other side. Examples of such disputes include mis-selling claims on complex financial derivative products and hedging solutions, LIBOR manipulation and fraud claims.

From 2005 to 2009, Alberto was head of Structured Products at the Royal Bank of Scotland in London, leading a team responsible for the structuring of synthetic credit derivatives products and customer driven solutions. In this capacity Alberto oversaw the development and execution of structured products such as CLOs, CDOs, credit default swaps, total return swaps.

From 2004 to 2005, Alberto led the Fixed Income team as Director, Head of Structuring at ABN AMRO. In this role, Alberto was responsible for the delivery of credit related solutions to institutional clients, for developing and executing regulatory capital and balance sheet solutions for global financial institutions, and for developing fund structure for the commercialization to private investors of structured products utilizing fund and insurance products platforms.

From 1997 to 2004, Alberto was at the UBS Limited as Fixed Income. Between 2003 and 2004 Alberto was Global Head of Structuring. In this role, Alberto led a team responsible for the Interest Rates and Credit Derivative Structured Products Desk.

Alberto began his career in New York, where he joined Credit Agricole in 1996 as an Associate in the Structured Products team.

Alberto holds two engineering Masters Degrees: from Ecole Centrale Paris, France and the Polythecnic of Turin, Italy. Alberto is fluent in Italian, French and Spanish.

A preliminary damages model.

As GDPR takes off, UK litigators may become frequent filers.

Evidence of collusive behaviour In academic publishing.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330