Research

Pre-Arranged Bids On Prepaid Cards

Assessing the impact of the cartel allegations.

In securities class action matters, an alleged misrepresentation is considered to have “price impact” if it affects the market price of the security. Price impact is closely linked to the concept of class-wide reliance on alleged misrepresentations, which plaintiffs must establish before a class can be certified. Since Basic v. Levinson, reliance is presumed for securities trading in efficient markets.1 However, following the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling in Halliburton II, defendants are allowed to rebut the reliance assumption with direct evidence that the alleged misrepresentations had no price impact.2

To evaluate price impact, two general approaches are possible. The first measures whether there is a “front-end” price reaction at the time the misrepresentations are made. The absence of a front-end price reaction, however, does not necessarily indicate an absence of price impact. For instance, if defendants fail to disclose a significant negative development, this may not lead to an immediate increase in price, but it could still have an impact by preventing the price from falling.

In such situations, a second, more indirect, approach is often applied. This entails analyzing the “back-end” price reaction at the time the truth emerges through corrective disclosures. Plaintiffs typically argue that back-end negative price reactions indicate that the initial misrepresentations indeed had a price impact.

In response, defendants often claim that the corrective disclosures are unrelated to the misrepresentation in terms of their content, and that, therefore, back-end price drops do not indicate front-end price impact. Prior to Goldman, lower courts often put little weight on such arguments at the class certification stage, viewing them as equivalent to an assessment of materiality or loss causation, which, since Amgen, are reserved for the later merits stage.3, 4

The Supreme Court’s 2021 Goldman order, which applies to the back-end approach described above, changed this. It ruled that, when the misrepresentation is generic (e.g., “we have faith in our business model”) but the corrective disclosure is specific (e.g., “our fourth quarter earnings did not meet expectations”), “it is less likely that the specific disclosure actually corrected the generic misrepresentation, which means that there is less reason to infer front-end price inflation—that is, price impact—from the back-end price drop.”5 More sweepingly, it stated that courts assessing price impact “’should be open to all probative evidence on that question—qualitative as well as quantitative—aided by a good dose of common sense.’ That is so regardless of whether the evidence is also relevant to a merits question like materiality.”6

Following the Supreme Court’s Goldman ruling, the case returned to the second circuit Court of Appeals. On August 10, 2023, that court released its own long-awaited ruling. Based on the Supreme Court’s guidance, it decertified the Goldman class, setting a potentially important precedent for other courts.7 The Court of Appeals argued that, in its previous certification of the class, the District Court had failed to properly factor in the mismatch in genericness between the alleged misstatements and the corrective disclosures.

In March 2023, similarly, the ninth circuit denied class certification related to a subset of allegations on grounds of a mismatch in genericness, citing the Supreme Court’s Goldman decision.8

An important question is whether defendants challenged price impact more vigorously at the class certification stage following Goldman. To answer the question, Fideres identified a preliminary sample of 90 10b-5 matters in which plaintiffs filed a motion for class certification between June 21, 2020 (one year prior to the Supreme Court ruling) and September 1, 2023. For each matter, we determined whether defendants filed an opposition to class certification, and if so, whether the filing challenged price impact.9

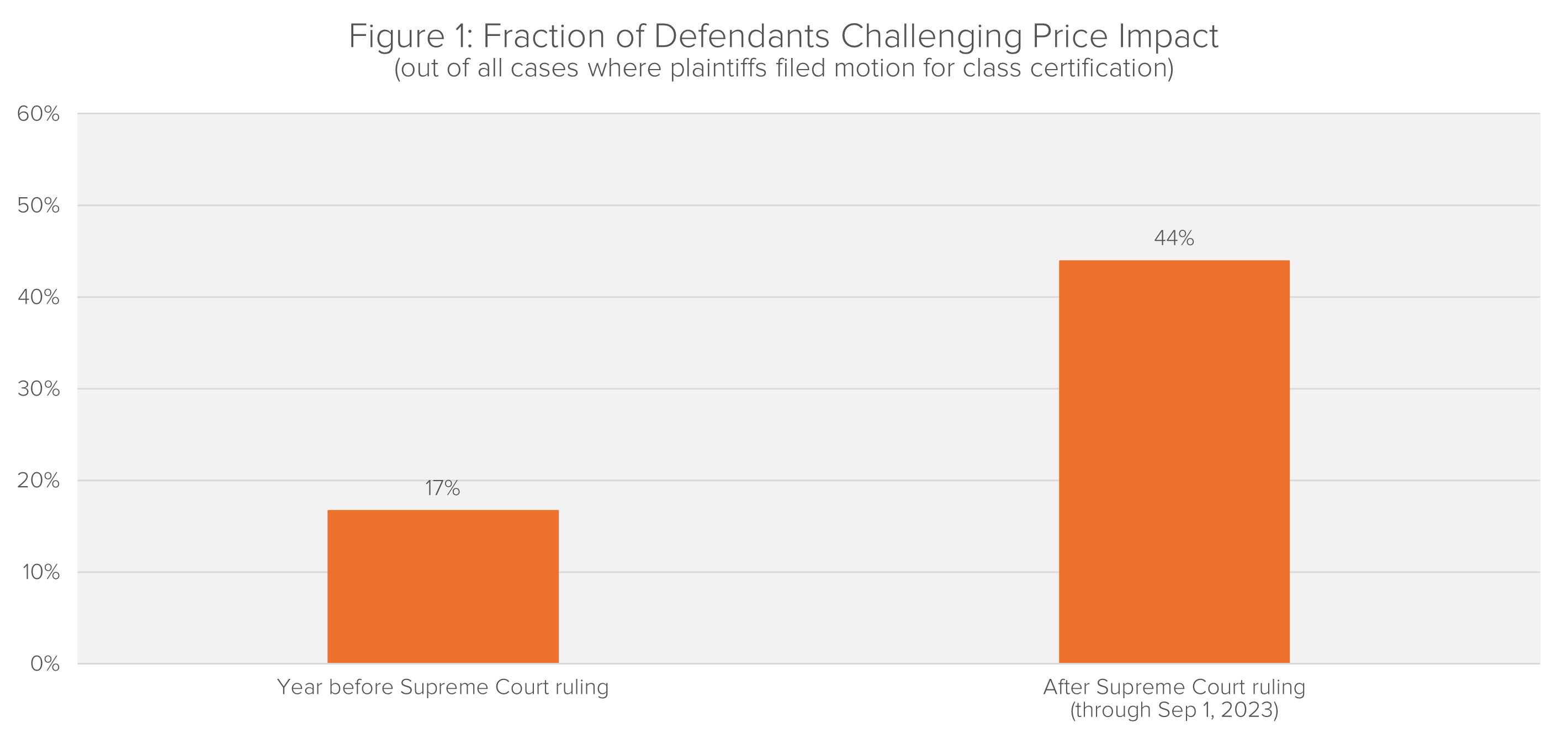

As Figure 1 and the table below show, defendants challenged price impact in 17% of the cases that reached the class certification stage in the year prior to the Supreme Court ruling. The corresponding number after the ruling is 44%, more than twice as high.10

Note: The first bar reflects 10b-5 cases where plaintiffs filed for class certification in the one-year period preceding the June 21, 2021 Supreme Court Goldman ruling. The second bar reflects cases where plaintiffs filed for class certification between June 21, 2021 and September 1, 2023.

Note: The first bar reflects 10b-5 cases where plaintiffs filed for class certification in the one-year period preceding the June 21, 2021 Supreme Court Goldman ruling. The second bar reflects cases where plaintiffs filed for class certification between June 21, 2021 and September 1, 2023.

| Filing Date for Plaintiff’s Motion for Class Certification | Number of Plaintiff Motions for Class Certification | Defendants Oppose, Challenging Price Impact |

| June 21, 2020 - June 20, 2021 (before Supreme Court ruling) | 24 | 17% |

| June 21, 2021 - September 1, 2023 (after Supreme Court ruling) | 66 | 44% |

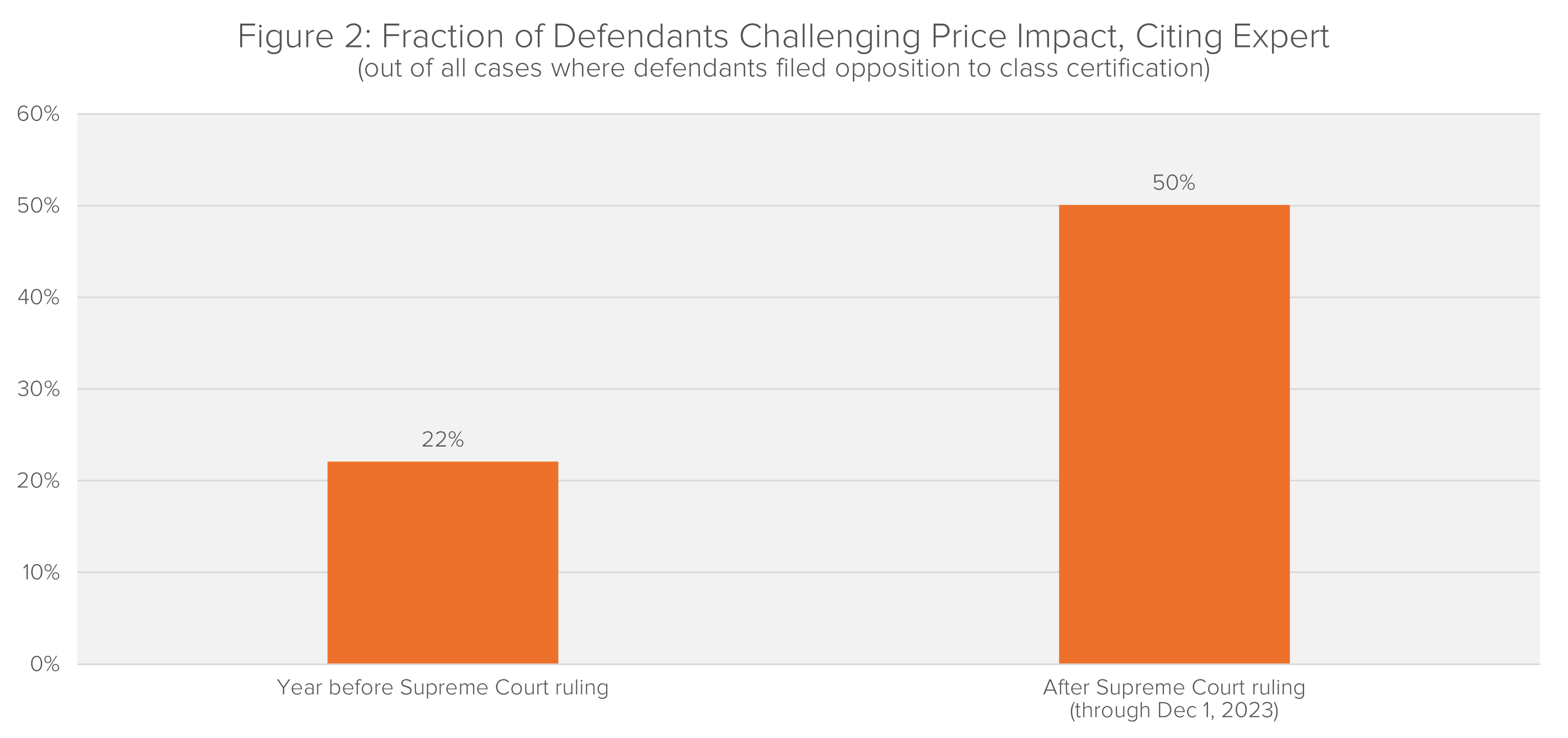

Fideres also analyzed defendants’ challenges to price impact. In the wake of the Goldman Supreme Court ruling, defendants increasingly provided detailed price impact analysis both at the front-end and at the back-end. Among defendants who filed an opposition to class certification in the year prior to the Supreme Court Goldman ruling, our preliminary analysis suggests that 22% relied on an expert witness to rebut price impact. This fraction more than doubled to 47% in the roughly two years between the June 21, 2021 Supreme Court ruling and the second circuit’s August 10, 2023 ruling. And in the four months following the second circuit ruling, 80% of defendants relied on an expert to challenge price impact. See Figure 2 and the table below. Together, these findings suggest defendants are spending considerably more resources challenging price impact at the class certification state following Goldman.

Note: The first bar reflects 10b-5 cases where defendants filed an opposition to class certification in the year prior to the June 21, 2021 Supreme Court Goldman ruling. The second bar reflects cases where defendants filed an opposition to class certification between June 21, 2021 and December 1, 2023.

| Fraction of Defendant Opposition Filings | |||

| Filing Date for Defendants' Opposition to Class Certification | Number of Defendant Oppositions to Class Certification | Challenging Price Impact | Challenging Price Impact, Citing Expert Report |

| June 21, 2020 - June 20, 2021 (before Supreme Court ruling) | 9 | 22% | 22% |

| June 21, 2021 - August 9, 2023 (between Supreme Court and second circuit rulings) | 57 | 51% | 47% |

| August 10, 2023 - December 1, 2023 (after second circuit ruling) | 5 | 100% | 80% |

| June 21, 2021 - December 1, 2023 (full period after Supreme Court ruling) | 62 | 55% | 50% |

At the heart of the Goldman class certification challenge was an alleged mismatch in the genericness of alleged misrepresentations and their corresponding corrective disclosures. However, defendants tend to cite to Goldman in a much broader context. In fact, our preliminary analysis suggest that only 21% of defendants challenging price impact argued that the alleged misrepresentations were overly generic relative to their corrective disclosures. Commonly, for example, defendants do not explicitly reference any mismatch and instead cite the Supreme Court’s recommendation that courts “should be open to all probative evidence” on price impact, “regardless whether the evidence is also relevant to a merits question like materiality.”11 Other times, defendants claim a mismatch along other dimensions than genericness.12

Fideres’ preliminary findings suggest defendants are markedly more likely to challenge price impact after the Supreme Court’s 2021 Goldman ruling. Defendants further appear to spend considerably more resources on their price impact rebuttal, reflected, e.g., by their increased reliance on expert witness reports following Goldman.

A future version of this article will analyze the impact of the second circuit ruling further and include an analysis of court orders on class certification.

1 Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988).

2 Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 573 U.S. 258 (2014).

3 Goldman Sachs Group v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, 141 S. Ct. 1951 (2021) (“Goldman”).

4 Amgen Inc. v. Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds, 133 S. Ct. 1184, 1195 (2013).

5 Goldman at 1961.

6 Goldman at 1961 (quoting In re Allstate Corp. Sec. Litig., 966 F.3d 595, 613 n.6 (7th Cir. 2020)).

7 Ark. Teacher Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., 2023 BL 275384, (2d Cir. Aug 10, 2023).

8 Goldman at 1961 (quoting In re Allstate Corp. Sec. Litig., 966 F.3d 595, 613 n.6 (7th Cir. 2020)).

9 Rather than challenging price impact directly, several motions argued that plaintiff’s expert had failed to describe a damages methodology capable of properly assessing the price reaction to misrepresentations and corrective disclosures. We did not classify such motions as challenging price impact.

10 The increase in defendants’ propensity to challenge price impact for a given case may be larger than what these numbers suggests, as the Goldman rulings may have caused plaintiffs to launch only class action suits with relatively strong evidence of price impact.

11 In re Qualcomm Inc. Securities Litigation, 2023 WL 2583306 (S.D. Cal. Mar 20, 2023).

12 In City of Birmingham Relief and Retirement System et al v. Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. et al (“Acadia”), for example, defendants argue that the alleged misstatement related to the design of a medical trial, while the associated corrective disclosure instead regarded the results of the same trial. See Acadia, Defendants’ Opposition To Plaintiffs’ Motion For Class Certification And Appointment Of Class Representatives And Class Counsel, October 20, 2023, pp. 21-22.

Steffen is a founding partner of Fideres with over 21 years’ experience in structured products and complex derivatives across all major asset classes. Steffen is responsible for the quantitative analysis of consulting mandates and has handled various complex benchmark manipulation cases, including LIBOR and ISDAfix, and cases relating to the mis-selling of structured product and derivatives. Prior to founding Fideres, he held a senior position at The Royal Bank of Scotland were he moved to after working for 5 years at Deutsche Bank. Steffen holds a master-level degree in Mathematics from the University of Erlangen, the Certificate of Advanced Studies in Mathematics (Part III) from the University of Cambridge and an MSc in Financial Engineering and Quantitative Analysis from the ICMA Centre at the University of Reading.

Assessing the impact of the cartel allegations.

Has enough been done to prevent future FX scandals?

Key Points In June 2023, the SEC published a complaint against Coinbase, a centralized cryptocurrency exchange that controls 76% of the market, all...

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330