Research

Can Algorithms Discriminate?

Fideres investigates algorithmic mortgage discrimination in the US.

In the 1995 Berkshire Hathaway (BH) annual meeting of shareholders, Warren Buffett explained his approach to investment using the “moat and the castle” metaphor:

“The most important thing […] we’re trying to do is we’re trying to find a business with a wide and long-lasting moat around it, […] protecting a terrific economic castle with an honest lord in charge of the castle.”

He claimed that all prosperous castles are subject to attacks from rival firms, and that understanding what keeps the castle standing is central to the work of holding companies like BH. While Buffett defines the “honest lord” as “low agency costs”, another interpretation for honesty is compliance with the law.

Achieving high barriers to entry can be a strategic goal for businesses seeking to establish a competitive advantage. One effective avenue to achieve that is to invest in innovation. A firm can come up with a brand-new product and take first-mover advantage in the market, or benefit from monopoly profits given by a new patent. Alternatively, big financial investment in research and development (R&D) can lead to higher efficiency and/or quality, creating a larger and deeper moat.

This is the system that competition aims to promote, leading to innovation and lower prices to consumers. In a competitive market, both new entrants and incumbents have an incentive to improve. New entrants have an incentive to come up with a competing product and gain market share. Dominant players, on the other hand, need to protect their market and keep up with consumers demands.

In June 2023, the SEC filed a complaint against Coinbase for violating the Exchange Act 1934,1 alleging that Coinbase acted as an exchange, broker, and clearing agency without registering as any of those functions.2 Moreover, Coinbase violated the Securities Act of 19333 by making available for trade at least 12 assets sold as securities without registering its offers and sales.4 These included tokens such as SOL, ADA, and DASH.

When performing the roles of exchanges, brokers, and clearing agencies, entities must satisfy specific requirements under the Exchange Act. The SEC found that Coinbase violated one of these requirements, by not segregating customers’ crypto deposits from other customer’s as well as the firm’s assets. The conduct may therefore have enabled trades that – if regulated properly –would not have been possible. Securities exchanges are also required to go through clearing agencies as intermediaries. Coinbase is alleged to have bypassed this rule and acted as both the exchange and the clearing agency for all trade occurring on the platform.5

By allowing users to earn financial returns – amounting to up to approximately 10% – Coinbase lured users into transferring their crypto assets to its exchange. As such, the SEC alleged that Coinbase’s Staking program consisted of a de-facto investment program for the five stackable cryptocurrencies offered by the platform, thus categorising them as securities.6 However, Coinbase did not register under the provisions of the Securities Act, and the SEC found that it profited from the program while offering unique features not available to those investors that were staking independently.7

While foreclosure through unlawful asset dealing is not the most traditional antitrust theory of harm, conduct that is illegal under other laws can have anticompetitive effects. Burning down your rival’s facilities is the most basic anticompetitive strategy to raise rivals’ costs.8 Similarly, Coinbase’s violations of US securities’ laws can also be analysed for its anticompetitive effects.

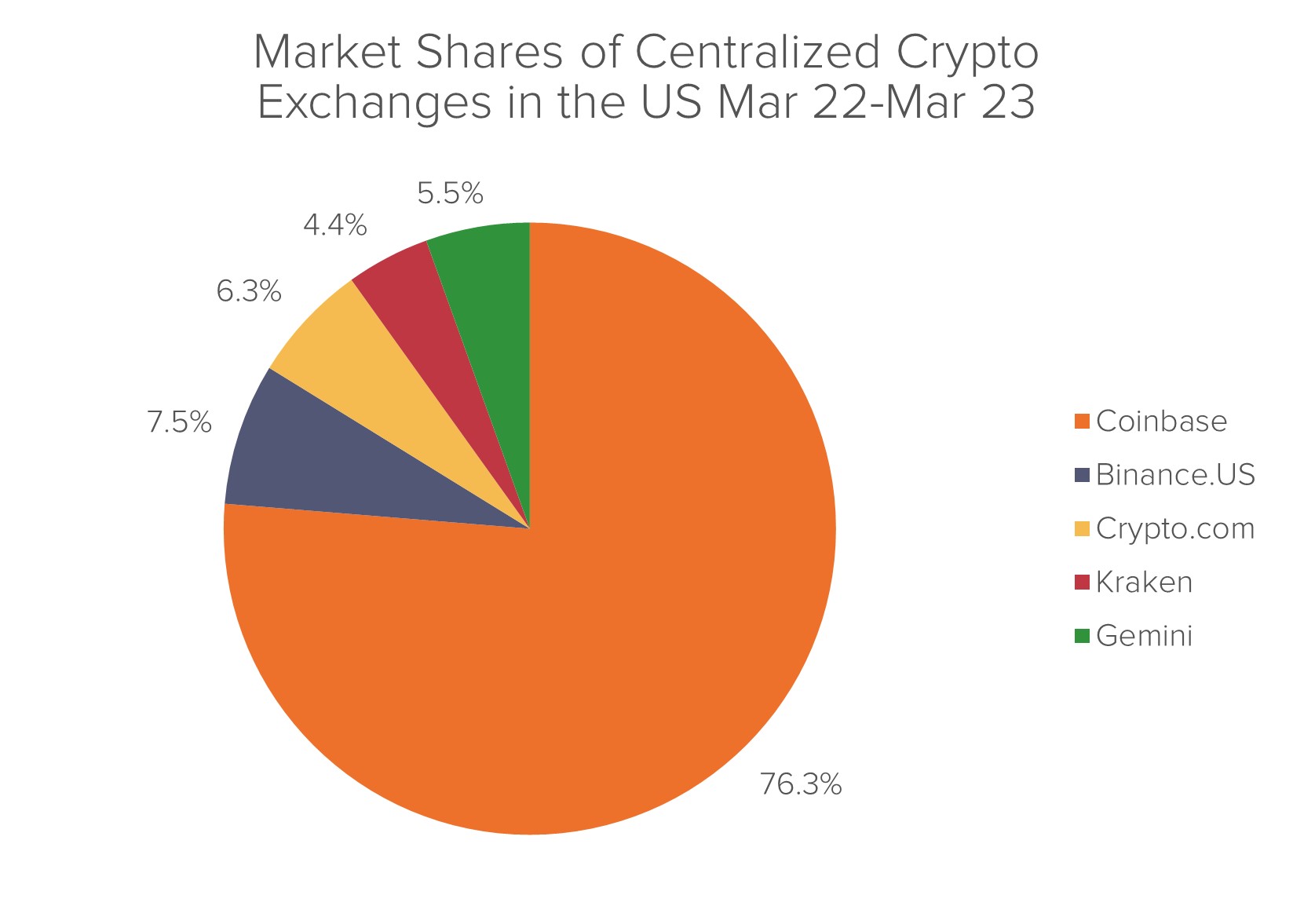

Coinbase is reported to have a market share of between 62% and 76% of centralized cryptocurrency exchanges in the US, indicating that it now has a monopoly in the market.

Source: US Crypto Exchanges’ Market Share | CoinGecko

Competition between platforms like Coinbase is driven primarily by users’ expected benefit from adopting the platform, which in turns depends on direct and indirect network effects, the size of the installed user base, and expectations about future adoption rates.9 In the case of cryptocurrency exchanges, attracting more buyers increases the value of the platform for sellers, and vice-versa, while more traders (buyers and sellers) increase the value of the platform for cryptocurrencies choosing to list their coins on the platform.

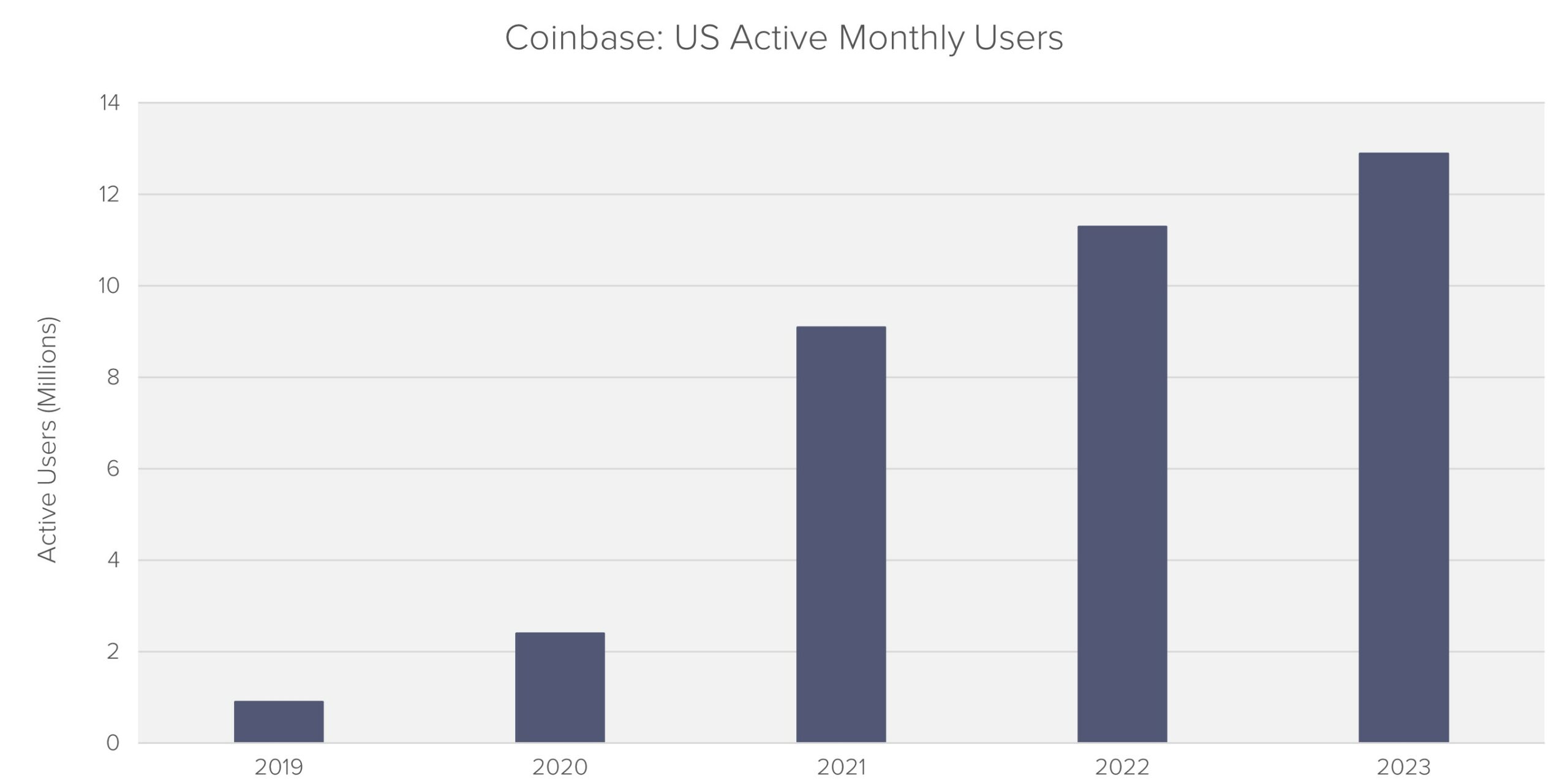

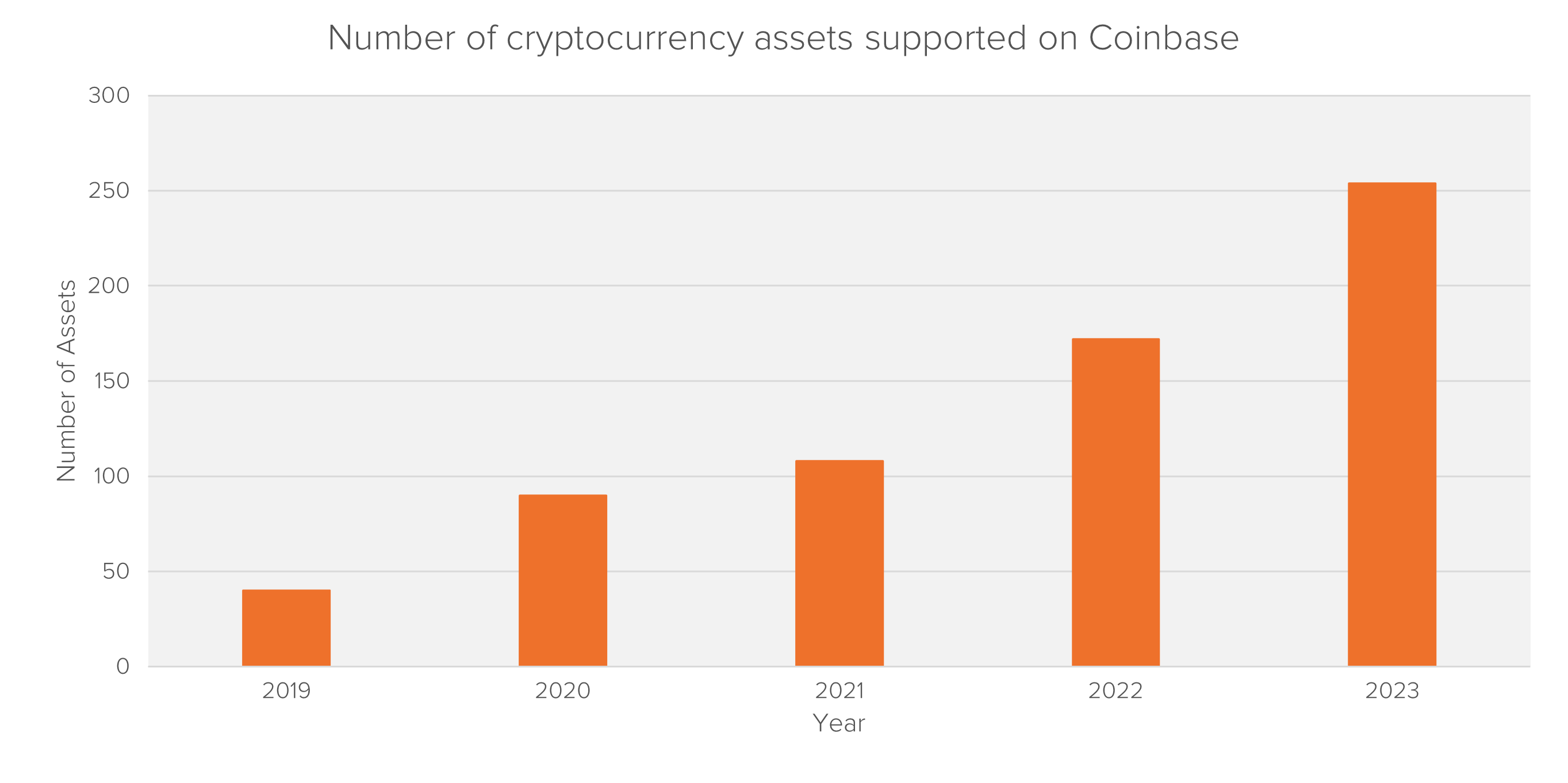

In the graphs below, the average number of monthly users active on Coinbase increased from 900,000 in 2019 to 9 million in 2021. At the same time, the increase in the number of users in 2020 saw a parallel increase in the number of available assets on the platform, which more than doubled from 2019 to 2020.

Source: US Active Coinbase Users, 2019-2023 (millions and % change) | Insider Intelligence, Coinbase Usage and Trading Statistics (2023) (backlinko.com) Document (sec.gov)

Source: US Active Coinbase Users, 2019-2023 (millions and % change) | Insider Intelligence, Coinbase Usage and Trading Statistics (2023) (backlinko.com) Document (sec.gov)

Network effects can be acquired by competing to offer a better, more innovative product or a cheaper price. In that case, consumer preferences strengthen exponentially as adoption increases, leading the best platform to become even more valuable than its rivals.10 This creates barriers to entry and market power for the platform in question, which may become visible in the form of inflated fees.

However, network effects can also be achieved through illegal conduct that forecloses rivals instead of competing with them. For example, predatory pricing,11 or, as in the case of Coinbase, the illegal provision of services on the platform. Each of these can build network effects and tip or monopolize a market, instead of competing for it. Once built, these network effects can then provide self-sustaining barriers to entry and expansion from rivals.

While monopoly prices built on competitively acquired network effects are perfectly legal (in the US), monopoly prices built on illegally acquired network effects are anticompetitive and could not be matched (or constrained) by an equally effective law-abiding competitor.

As well as its illegal offering of exchange, brokerage, and clearing services, the SEC also alleged that in the examined period (2019-2022), Coinbase offered a Staking Program in most of the US for five tokens.12 Coinbase’s Staking Program attracted traders, increase momentum, and strengthened the network effects and hence the size of the moat. Between Q1 and Q2 2021, the adoption of the Staking Program increased more than 300%, reaching 1.7 million customers,13 and the end of 2021, the total value of crypto assets committed by investors amounted to approx. $28.7 billion.

In 2022, the number of users “investing” in the staking program reached over 4 million. Kraken, one of Coinbase’s competitors in the US, used to also offer a staking program until February 2023, when the program was discontinued in its US operations, following a SEC complaint regarding the unregistered staking program operating with “crypto securities”.14

The choice by Kraken to close the program because of the complaint, and not to instead register it and provide disclosure and investor protection, helps illustrate that no equally efficient law abiding competitor could adopt the same practices in order to build their own network effects.

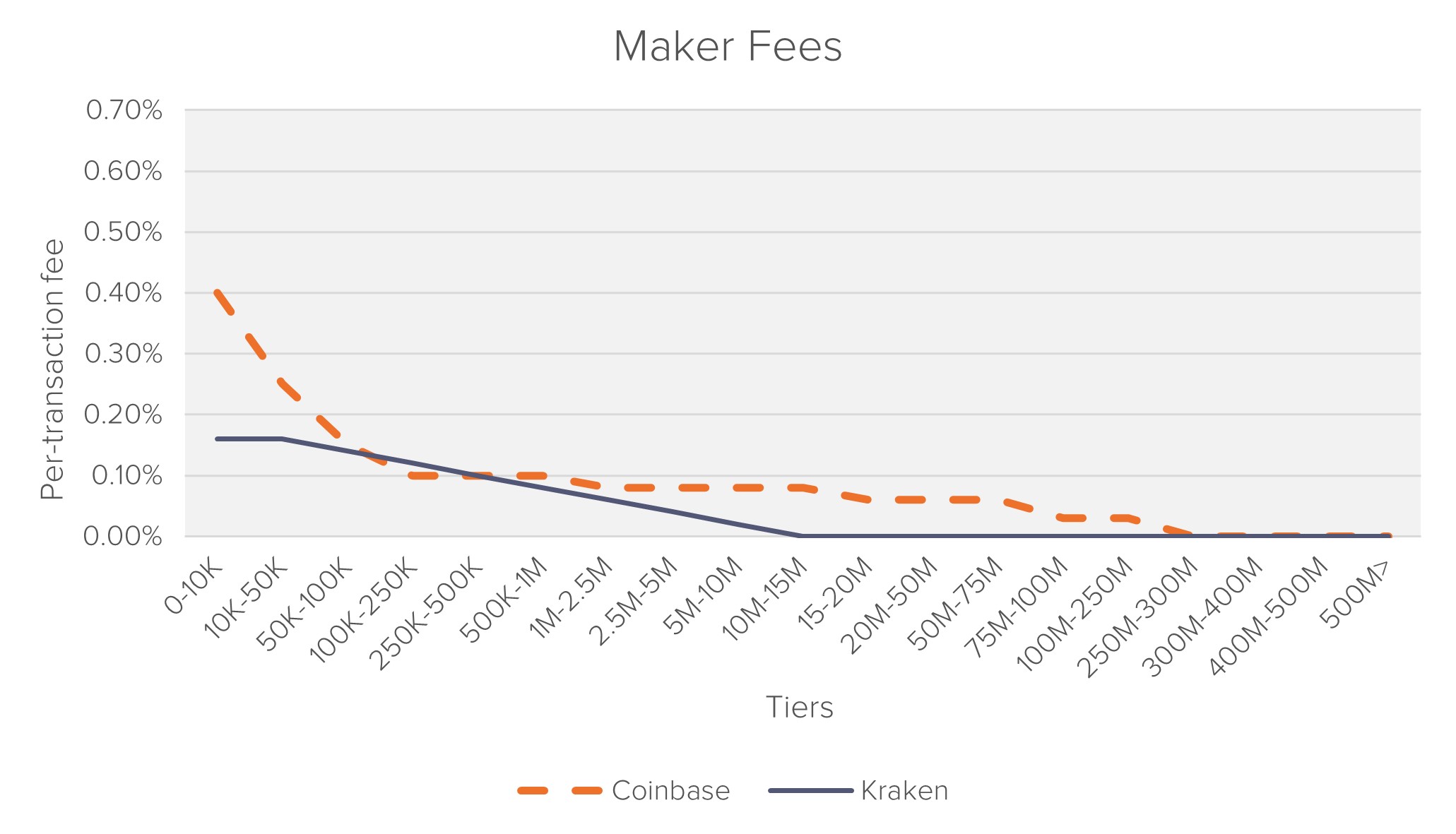

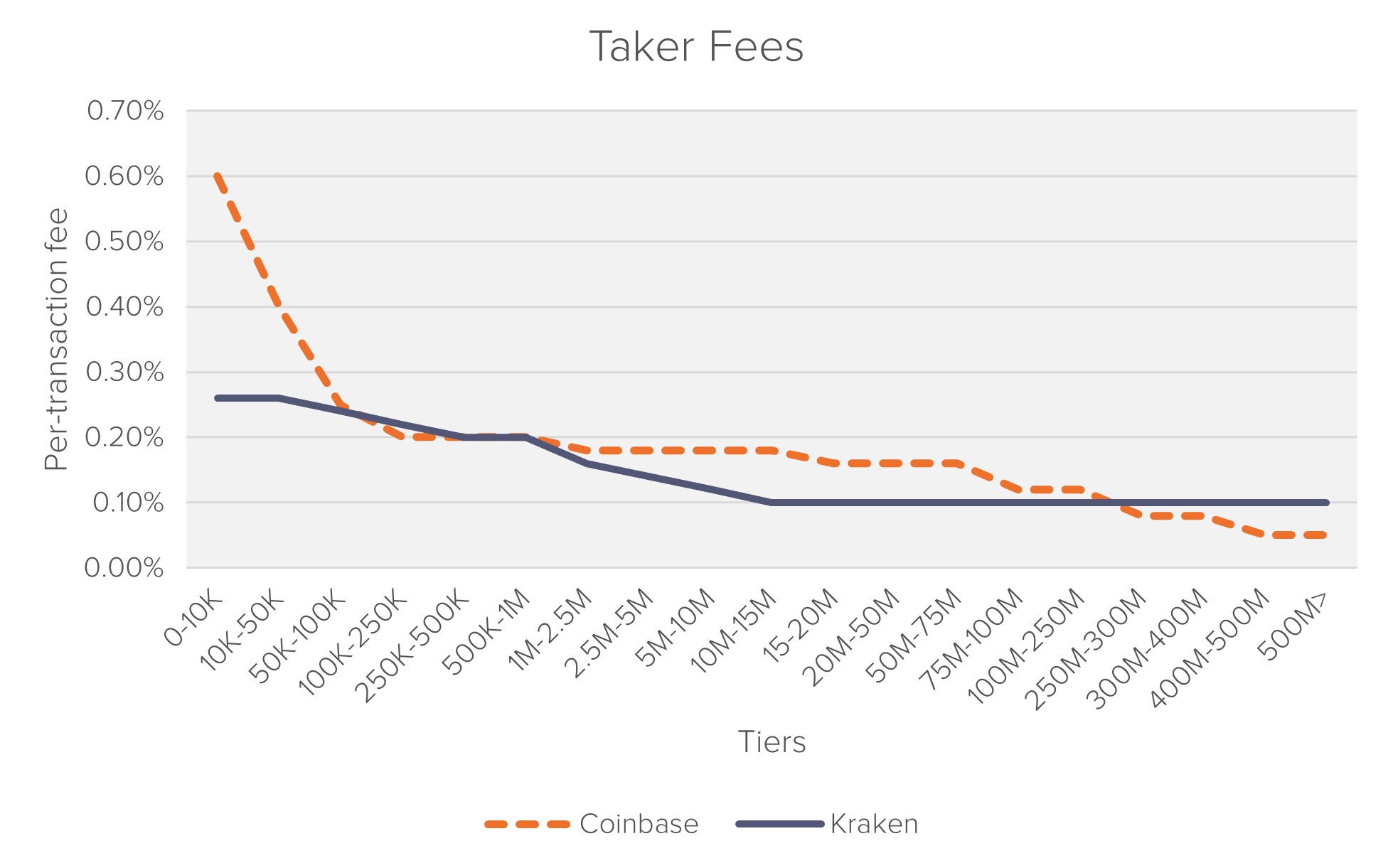

In the US market, centralised cryptocurrency exchanges like Coinbase charge fees per transaction that vary by the transaction value. They also distinguish between maker and taker fees (i.e. fee paid by buyer or seller depending on matching offer availability).15 Thanks to the market power it reached through its anticompetitive conduct, Coinbase has been able to set significantly higher fees compared to its competitors. As shown below, when compared to Kraken fees, Coinbase’s fees are much higher for low value transactions, are broadly comparable for middle value transactions, and are again higher for the high value transactions.

Figures: Maker and Taker fees by transaction value16

We estimate an overcharge on maker fees and taker fees as high as 73% and 30% for small volume transactions, respectively.

Fraud in the cryptocurrency market comes with no surprise. Exchanges like FTX17 and Binance18 have been investigated by the SEC over the past couple of years, with the former ultimately filing for bankruptcy. This commentary suggests that violations of SEC regulations by Coinbase should also be examined from an antitrust perspective. Network effects ought to be established via fair competition, low prices, enhanced efficiency, and innovation. Castles relying on fraudulently obtained moats ought to be torn down by the townsfolk – since they breed lazy, incompetent and exploitative rulers.

1 Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 48 Stat. 881, 15 U. S. C.

2 “Coinbase violated section 5, 15 (a) and 17A(B) of the Exchange Act [15 U.S.C. §§ 78e, 78o(a), and 78q-1(b)(1)], and for purposes of Coinbase’s violations of the Exchange Act, CGI was a control person of Coinbase under Exchange Act Section 20(a) [15 U.S.C. § 78t(a). It has also violated Sections 5(a) and 5(c) of the Securities Act [15 U.S.C. §§ 77e(a) and 77e(c)].” SEC vs. Coinbase, Inc and Coinbase Global, Inc Coinbase, Inc. and Coinbase Global, Inc. (sec.gov)

3 Securities Act of 1933, 48 Stat. 74, 15 U. S. C.

4 These 12 securities are, by trading symbol: SOL, ADA, MATIC, FIL, SAND, AXS, CHZ, FLOW, ICP, NEAR, VGX, DASH, and NEXO. Coinbase, Inc. and Coinbase Global, Inc. (sec.gov), page 33.

5 Ibid.

7 Coinbase, Inc. and Coinbase Global, Inc. (sec.gov)

8 See Baker, Jonathan B. “Exclusion as a core competition concern.” Antitrust LJ 78 (2012): 527, page 13.

9 Developing network effects for digital platforms in two-sided markets – The NfX construction guide – ScienceDirect

10 (PDF) Endogenous Timing and Intensity of Inertia in a Bandwagon Equilibrium (researchgate.net)

11 See Fletcher (2007): https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=987875

12 Coinbase, Inc. and Coinbase Global, Inc. (sec.gov)

13 0001679788-21-000026 (d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net), page 43.

14 SEC.gov | Kraken to Discontinue Unregistered Offer and Sale of Crypto Asset Staking-As-A-Service Program and Pay $30 Million to Settle SEC Charges and On-chain staking eligibility and availability | Kraken

15 Coinbase Fees: A Full Breakdown and How To Minimize Costs | GOBankingRates

16 Source: Coinbase Pro | Digital Asset Exchange ; Fee Structures | Explore our trading fees | Kraken

17 https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/11/business/ftx-bankruptcy.html

18 https://www.reuters.com/legal/binance-heads-court-seeking-dismissal-sec-fraud-lawsuit-2024-01-19

Gabriele joined Fideres in 2022, while completing a Master of Public Policy at the University of Chicago as a Fulbright Scholar. He specialises in market regulation, focusing on competition in digital markets. At Fideres, he has contributed to cases of price fixing, monopolisation, MFN, multisided-markets, and algorithmic collusion. Before starting his Master’s program, Gabriele lived in Tokyo for five years, where he directed the monitoring and evaluation of one of Japan’s largest nonprofits. He speaks five languages, including Japanese, and is passionate about technology and innovation. Gabriele is also an “Economic Ambassador” to the Antitrust division of the American Bar Association (ABA).

Fideres investigates algorithmic mortgage discrimination in the US.

Defining markets for loyal customers.

Estimating pass-on damages.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330