Research

More Than Poultry Profits

A Fideres Special Antitrust Investigation into the UK CO2 Market.

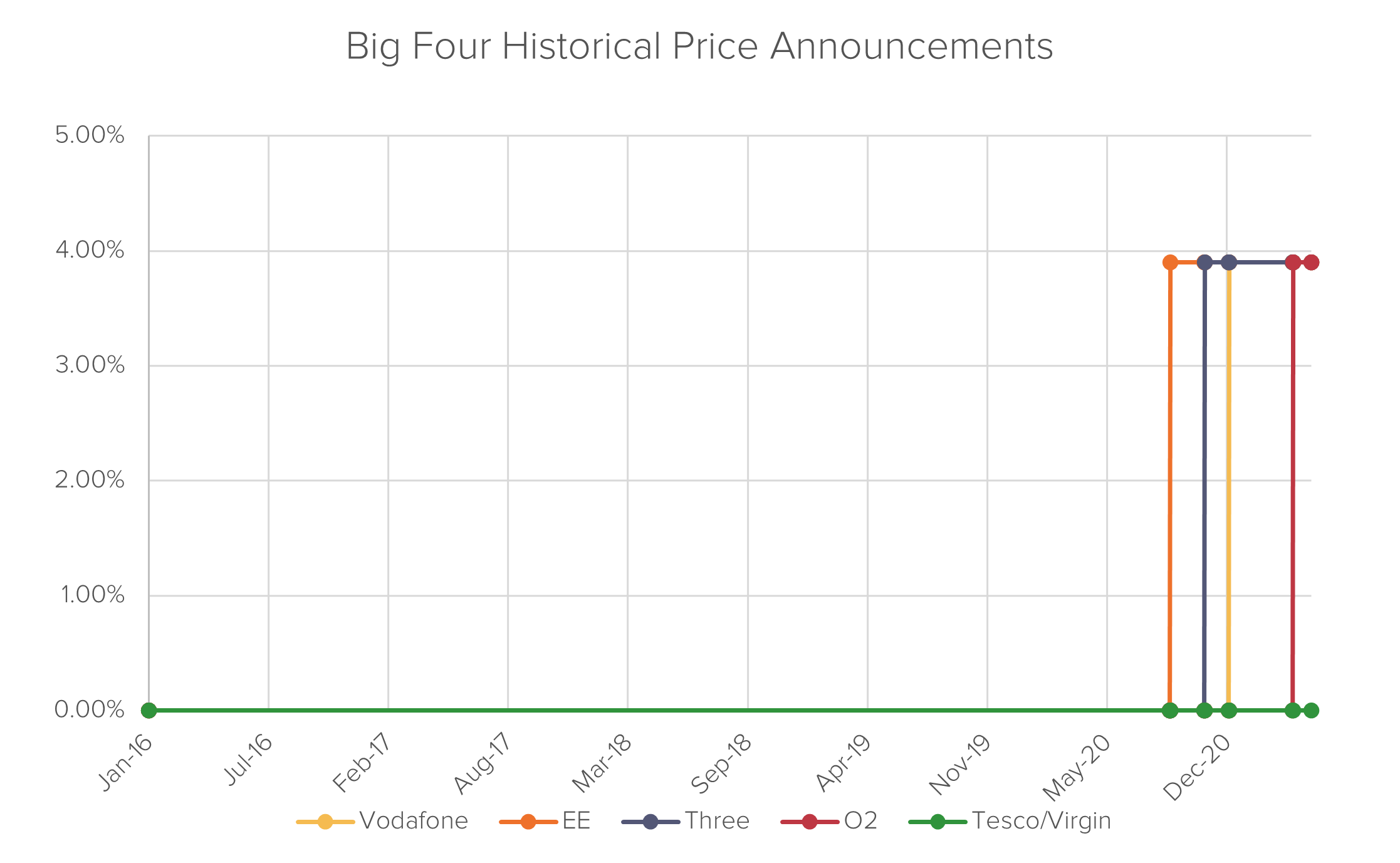

Fideres has conducted a preliminary investigation into UK mobile network operators. This follows the four largest UK mobile network operators – EE/BT, O2, Vodafone and Three – concurrently raising prices to their pay monthly fixed term contracts. We have found that:

In October 2020, EE and BT Mobile (which jointly have a 28% market share according to BT’s 2018 annual report1 announced that any new fixed term pay monthly contract would have a provision for the automatic increase of contract prices on the 1 April each year. The rate of increase is specified to be RPI +3.9%. Based on the March RPI index, this translates into a price increase of 4.5%. Plusnet, also owned by BT, has implemented an identical price increase as of October 2020.

O2 and Vodafone, representing 26% and 21% of the market, respectively, followed suit and introduced identical provisions. Three, with a market share of 12%, introduced the same rate of increase, but instead of referencing the inflation index, they specified it to be equal to 4.5%, also to kick-in on 1 April (incidentally, 4.5% is equal to RPI +3.9% for this year).

It does not appear that these contract changes have also been imposed on customers with older contracts.

Together, the top four mobile operators represent over 87% of the market. Two smaller operators – Virgin Mobile and Tesco Mobile – did not introduce similar amendments to their contracts. Virgin Mobile maintained a price increase equal to RPI, while Tesco Mobile continues to maintain constant prices throughout the term of the contracts.

Price increases of this magnitude have not been introduced in other European markets. Our research shows that annual contract price increases in the EU/EEA are typically aligned with the respective national inflation index. Mobile phone price hikes above the rate of inflation are a UK anomaly.

In the UK, there are two types of mobile phone service providers:

MVNOs tend to offer a more narrow range of services compared to MNOs. MVNOs tend to compete on basic mobile packages such as sim-only plans but may not be a pure competitor to MNOs when it comes to the market for full-service plans. A 2015 Ofcom Strategic Review of Digital Communications Study mentions differences in services used by MVNO customers compared to MNOs2.

EE was borne out of the merger between T-mobile and Orange in 2009. The CMA approved the acquisition of EE by BT in January 2016. In the same year, the European Commission (EC) blocked a proposed merger between O2 and Three. In May 2020, the EU General Court annulled the EC’s decision to block the merger3, finding that the relevant standard of proof of the impact of the proposed merger relating to prices and quality was not met. The EC has appealed this decision to the European Court of Justice. On 14 April 2021, the CMA provisionally cleared the merger of Virgin and O24 and on 20 May 2021, the CMA gave the green light for the merger to take place5. Following the merger, it will be interesting to observe whether Virgin Mobile will maintain price increases at RPI, or align the price increases with O2.

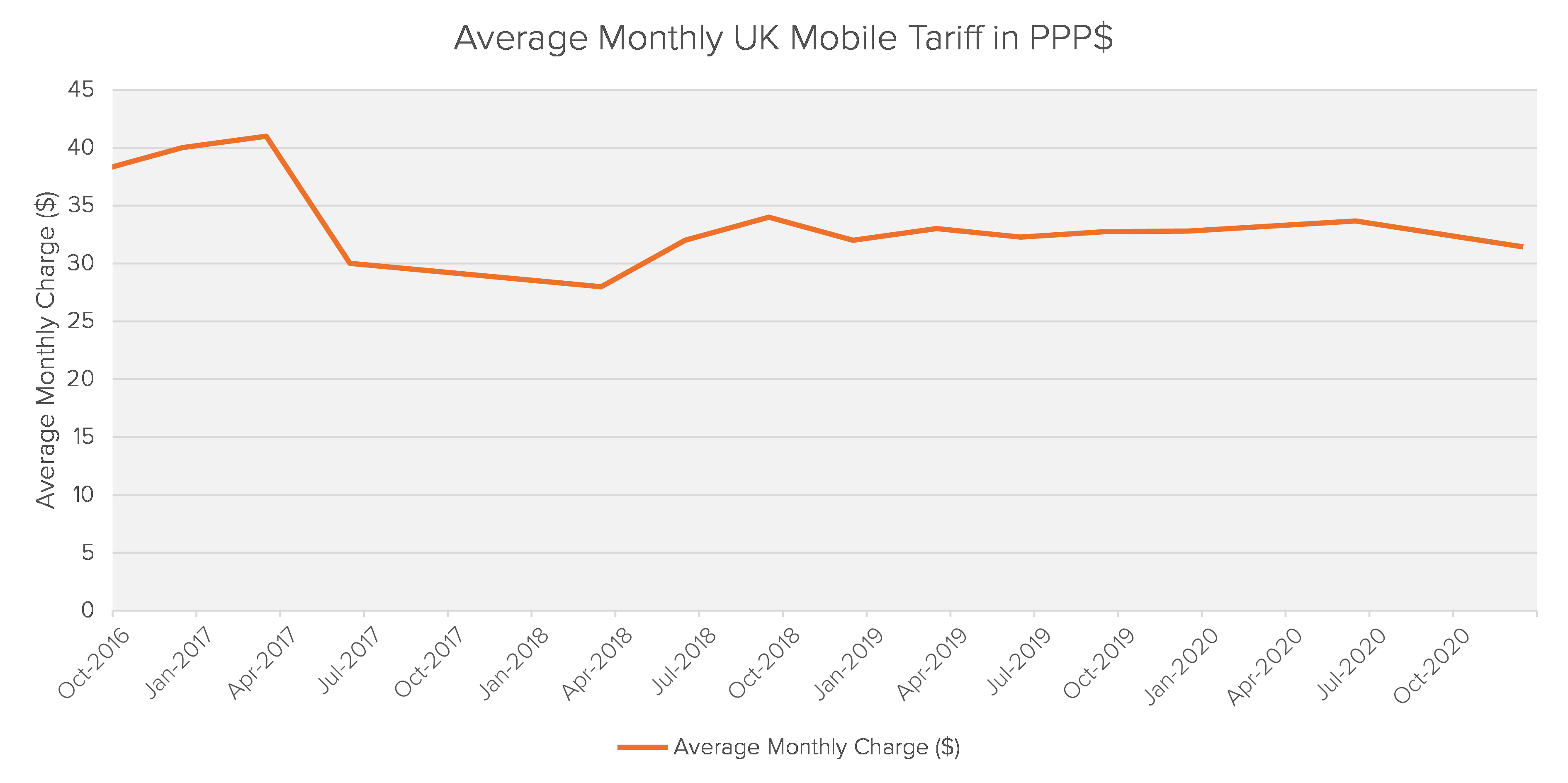

Competition and pro-competitive policies such as the EU ban on roaming charges6 have led to a compression on profit margins for mobile network operators for the past 20 years. Since 2016, prices for mobile services in the UK have been relatively stable.

Source: Point Topic

Source: Point TopicThe Big Four have motivated the parallel price increases with the large investment required to roll out 5G technology across the UK. Given that Vodafone and Three operate networks across several EU countries, if the motivation for the price increases is the cost of 5G implementation, why have they not announced similar price increases in other markets? The answer most likely lies in the relatively higher level of competition in EU markets compared to the UK. The pro-consumer stance of the ECJ, in relation to contract law, could also make unilateral, mid-contract price increases harder to implement.

Approximately 50% of all pay monthly contracts have an initial fixed term of 24 months, while the remainder of the contracts are approximately equally split between 12 months and 1 month rolling terms.

Until October 2020, all contracts had a maximum annual increase equal to RPI/CPI. It is only then that mid-contract price hikes are introduced.

Regardless of the initial term of the contract, Ofcom data shows that a large proportion of customers do not switch contracts at the end of the initial term. Ofcom’s annual Switching Tracker for 2020 highlighted that 39% of the consumers with a mobile phone contract never switched providers7.

The identical terms proposed by all major networks could generate a reduction in competition through a stabilization of market share: if all MNOs increase prices at the same time every year, there will be less incentive for consumers to shop around. It remains to be seen, but if MNOs also increase the initial price of the plans in line with the RPI +3.9% stipulated in the contract, switching provider will no longer protect consumers from the “loyalty penalty”.

Following a consultation, in 2013 Ofcom ruled that, as long as price increase clauses are clear and transparent, they are legal and do not give rise to an optional termination for consumers. This is radically different from the stance taken by other regulatory agencies:

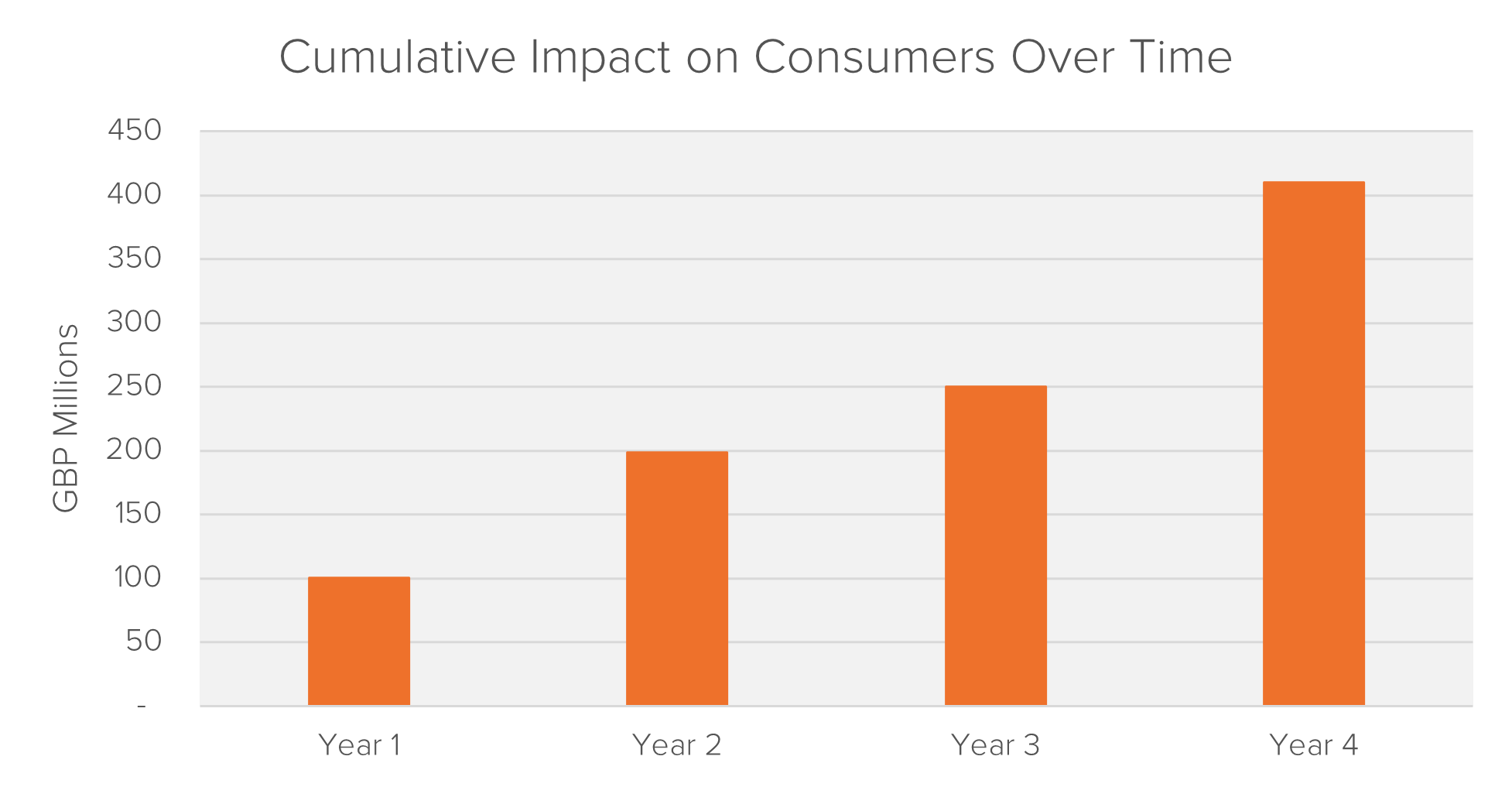

In a December 2018 report, the CMA highlighted the impact of loyalty penalties, where companies penalize customers who stay on their contracts for the long-term compared to customers who switch. The impact of these latest mobile contract price changes seem to be a reverse of the loyalty penalty, and instead can be thought of as a switchers penalty. Not only will a growing number of consumers (up to 40% of consumer switch contracts) be affected over the coming years, but the significant change in contractual price increases will complicate consumers’ decision making process.

If, as we expect, the Big Four’s contract changes lead to reduced price competition, consumers with expired contracts will be better off remaining on their old plans instead of new offers. The 3.9% increase above inflation imposed by the new contracts will quickly erode any potential savings offered by the new plans. Giving up an old contract, where price increases are capped at RPI or CPI, could be very costly to consumers.

The chart below illustrates Fideres’s projected impact on UK consumers of the contract changes introduced.

Source: Fideres Calculations, Ofcom

Source: Fideres Calculations, OfcomThis raises a number of questions:

When taken as a whole, the evidence gathered might be indicative of anti-competitive conduct on the part of the four largest mobile network operators in the UK.

Fideres has filed a complaint with Ofcom and the CMA to take rapid action to investigate mobile network operators’ conduct. As the economy recovers from the COVID-19 slump, it is crucial that competition in the mobile network sector is retained to maintain the UK economy competitiveness against Europe and other major economies.

Rahul joined Fideres in 2019 after completing his MSc in Economics from the University of Warwick. Since joining Fideres, Rahul has been building his expertise in securities litigation and competition litigation in sectors including publishing, pharmaceutical and digital markets. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Computer Science and Engineering and has worked as a software engineer prior to joining Fideres. He brings this expertise in programming and technology into economic analysis as well, building database models and analytic frameworks for quicker and more efficient analysis.

A Fideres Special Antitrust Investigation into the UK CO2 Market.

Evidence of collusive behaviour In academic publishing.

ISDAFix is the latest financial benchmark to have allegations of financial manipulation made against it.

London: +44 20 3397 5160

New York: +1 646 992 8510

Rome: +39 06 8587 0405

Frankfurt: +49 61 7491 63000

Johannesburg: +27 11 568 9611

Madrid: +34 919 494 330